Now Boarding

Brightline, originally known as All Aboard Florida, is a fast-speed passenger rail service developed by a company that traces its roots to industrialist Henry Flagler, who built a pioneering railway along Florida’s eastern coast more than a century ago.

Now it appears the new railroad is giving a lift to not only increasing numbers of passengers but real estate investors and owners, according to a Bergstrom Real Estate Center analysis of thousands of property transactions near Brightline rail stations between 2009 and 2022.

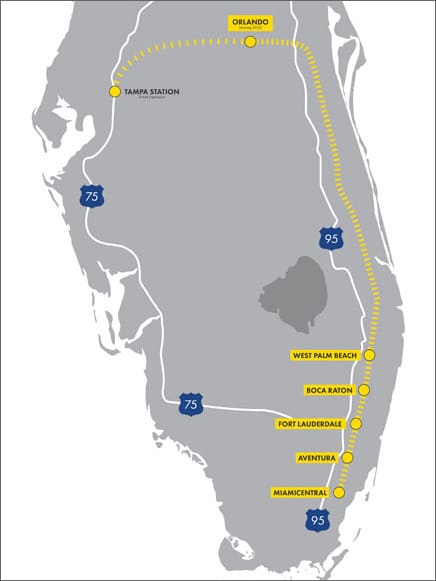

The activity is coming more than a decade after Brightline’s parent, Florida East Coast Industries, announced plans to relaunch passenger service along Flagler’s old tracks to connect South Florida population centers with Orlando. The opening of the first phase linking Miami, Fort Lauderdale and West Palm Beach was delayed until 2018 and then derailed for 1 years during the COVID-19 pandemic. But Brightline has since picked up steam: in December it opened stations in Aventura and Boca Raton, and it is on track to launch service to Orlando International Airport before summer’s end. Touted as the nation’s only privately owned and operated intercity passenger railroad, Brightline aims to change people’s behavior by offering an alternative for those tired of congested highways or prefer an option they view as more environmentally friendly.

To get this far, Brightline has spent roughly $5 billion on what is a complex operation to provide modern train service on the 235-mile route. It renovated old tracks, constructed new ones, and completed extensive infrastructure work involving grade crossings, bridge modifications and installing a second track along its right-of-way. It built coalitions with many government jurisdictions and transportation agencies, and fought and settled lawsuits over its expansion plans and safety measures. It purchased sleek diesel-electric trains and is testing accelerating them up to 125 mph on the last segment to Orlando International. The railroad wants to eventually extend service to Tampa, with a preferred route along the Interstate 4 corridor and State Road 528 toll road.

- March 2012: All Aboard Florida, later renamed Brightline, announced

- May 2014: Miami station construction starts

- October 2014: Ft. Lauderdale station construction starts

- March 2016: West Palm Beach construction starts

- January 2018: Service begins between West Palm and Ft. Lauderdale

- May 2018: Service begins to Miami station

- June 2019: Construction of Phase 2 starts between West Palm Beach and Orlando

- October 2019: Aventura station announced

- December 2019: Boca Raton station announced

- March 2020: Temporary shutdown of service due to COVID-19

- September 2020: Aventura station construction starts

- November 2021: Reopens South Florida segment

- January 2022: Boca Raton station construction starts

- December 2022: Aventura and Boca Raton stations open

- April 2023: Unveils Orlando station (among those attending: Brightline founder Wes Edens)

- May 2023: Begins selling tickets on the Orlando segment for travel beginning Sept. 1

Leveraging rail

Underpinning the entire project is Florida East Coast’s real estate development strategy. The company positioned itself to leverage the rail service to increase the value of its extensive land holdings around the stations and along the rail corridor. Building stations in Miami, Aventura, Fort Lauderdale, Boca Raton and West Palm Beach were significant real estate developments on their own.

A notable example is Florida East Coast’s MiamiCentral, a mixed-use development spanning six blocks surrounding its downtown Miami station. In 2019, Florida East Coast sold two office towers at MiamiCentral to a San Francisco property company for reportedly $159 million. Just two years later, the investment giant Blackstone Group paid $230 million for the 330,000 square feet of office space. Florida East Coast also built multifamily residential properties under the brand name ParkLine — 816 units with two towers perched above MiamiStation and 290 more units in a tower in downtown West Palm Beach. Last year, Florida East Coast sold its Miami apartment towers to Harbor Group International for reportedly $450 million. Without confirming the price, a Brightline spokesman said it represented “the highest gross sale price for a residential property in the history of the Southeast U.S.” This followed on the heels of Florida East Coast’s sale of its West Palm Beach apartment tower and 14,000 square feet of retail space to an affiliate of New York Life Real Estate Investors for reportedly $115 million. “Our investment in real estate was designed to initiate train ridership and help spark new projects around our stations,” Ben Porritt, senior vice president of corporate affairs at Brightline, said in an emailed statement. “The investment made by Brightline has spurred significant commercial and residential growth as proof that transit-oriented development works, and more is needed.”

Another potential impact of Brightline on the real estate market is its influence on affordable housing initiatives. While the fast-speed rail service attracted considerable interest from developers, the South Florida Housing Link Collaborative, a nonprofit group, sought to counteract potential displacement of low-income residents. In 2019, the group obtained a $5 million investment pledge from JPMorgan Chase to build 150 affordable rental units and renovate 50 existing units along Brightline’s rail corridor. These equity and access initiatives suggest that transit projects like Brightline may also have the potential to drive inclusive urban development.

Porritt said, “Brightline’s stations have led to thousands of new units – including affordable housing – and has regenerated areas of Miami and South Florida that hadn’t been redeveloped in decades.”

Our analysis

Motivated by these developments, we analyzed the impact of the Brightline rail route on the South Florida real estate market. We focused on residential and commercial properties located in the neighborhoods surrounding the five South Florida stations: Miami, Aventura, Fort Lauderdale, Boca Raton and West Palm Beach. We defined two groups based on distance to the nearest station: of a mile or less, which is a reasonable walking distance of roughly 15 minutes, and between to 1 mile. (We determined the distances using the centroid of the census block group in which a property is located and the geographical coordinates of the nearest station.)

The first part of our analysis focused on properties built before March 2012 — prior to Brightline announcing the rail service. This was to isolate the potential impact on the value of existing properties from the impact on new development. For each station, we specified three relevant events: (1) public announcement; (2) beginning of construction; and (3) opening of the station. Using data on arm’s length transactions from the Florida Department of Revenue’s property tax data between July 2009 (the end of the Great Recession) and 2022 (our most recent data), we compared the transaction prices of properties in our two distance groups, before and after the relevant events. The final sample for the residential sector consisted of 7,494 transactions in the region closest to the stations and 10,810 in the outer ring over the 13-year time frame. Aggregated across all five markets, approximately two-thirds of the property transactions we examined were condominiums, one-fifth were single-family homes and just below 10% were multifamily units. For the commercial sector, the number of transactions was much smaller, 171 observations in the region closest to the stations and 595 in the outer ring.

Our results for the residential sector indicate that properties located closer to a station sold at a 13.4% premium following the announcement of the future station compared with properties in the outer ring. Similarly, the announcement of the opening of a station displayed a positive impact with the price of those closest to the stations garnering 10.4% more than those farther away. On the other hand, the beginning of construction showed a negative impact on prices of -13%. Nevertheless, when aggregating these effects, the overall impact was roughly a 9% premium of residential property prices located closest to a Brightline station. We note that Aventura and Boca Raton stations opened in December 2022, after the end of the data.

These results suggest that proximity to a station significantly boosted property appreciation. In a simpler comparison, Figure 1 illustrates how average transaction prices increased relatively more in the regions within walking distance to Miami, Fort Lauderdale and West Palm Beach stations, when comparing the 12 months before and after the opening of these stations.

With respect to commercial properties, our analysis was limited by the much lower number of transactions observed and greater variability in values. For instance, we have data on only 171 transactions between 2009 and 2022 in the regions closer to the stations. In addition, the value of commercial property is affected to a much greater extent by distance to a high-traffic location, which means that the -mile cutoff is likely to be more relevant for the analysis of the residential sector. Nevertheless, our analysis indicates that following the announcement of a Brightline station there was a large positive impact on transaction values of surrounding commercial properties. Our best estimate is that this impact was roughly 100%, although we are cautious about interpreting the exact number due to the small sample used. Beginning of construction and the actual opening of the station did not display a statistically significant impact on transaction prices of commercial properties.

Note: Data for regions of Miami, Fort Lauderdale and West Palm stations

Sources: Bergstrom Real Estate Center based on data from the Florida Department of Revenue

Transactions

In addition to values, we examined the number of transactions of existing residential properties over time to see whether there was a noticeable heating up of the market in the regions within walking distance to the stations. Figure 2 displays separate time trends for the inner and outer regions, and highlights the times when Brightline was first announced and when it started operating. The results suggest that in the two years following the announcement there was a slight relative increase in the volume of transactions of properties closer to the stations, although the difference was not statistically significant. Later, there does not appear to be a substantial difference between the two trends.

Total residential property transactions near Brightline rail stations in Miami, Fort Lauderdale, West Palm Beach, Aventura and Boca Raton.

Sources: Bergstrom Real Estate Center based on data from the Florida Department of Revenue

Finally, regarding new development, we investigated whether the placement of the stations incentivized new construction of residential properties, motivated by the anecdotal cases presented above. Using property tax data from the Florida Department of Revenue, we compared the average and median age of properties closer and farther to the stations. In case there was substantially more development happening closer to the stations, we would expect the average age of properties to decrease in this region relative to the alternative. Surprisingly, the data shows the opposite trend, with the average age of properties decreasing relatively faster in the neighborhoods farther to the stations during the period after Brightline was announced (Figure 3). Nevertheless, while there may not have been a sustainable increase in the volume of transactions or a greater spur of new development in the vicinity of the stations, nearby residential and commercial properties experienced substantial appreciation due to the establishment of a rail route.

Sources: Bergstrom Real Estate Center based on data from the Florida Department of Revenue

Sources: Bergstrom Real Estate Center based on data from the Florida Department of Revenue

All in all, Brightline undeniably attracted considerable attention to the markets it serves and may have motivated specific investment activities. The story of Brightline’s impact on South Florida’s real estate sector demonstrates how transportation infrastructure can influence urban development and reshape real estate markets.

It remains to be seen whether the railroad makes a major impact on the behavior of travelers as it throttles ahead. In May, Brightline started selling tickets for travel starting Sept. 1 between Miami and Orlando, though the exact launch date is pending regulatory approval. The schedule shows 16 trains a day with fares ranging from $79 to $149 each way for the 3 -hour trip.

Author:

Fernando Mattar is assistant director of data management for the UF Bergstrom Real Estate Center.

A Tycoon and a Train Transformed the Sunshine State id="supplement"

By Charles Boisseau

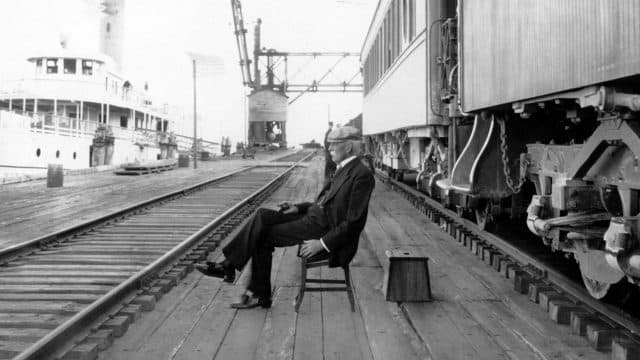

If there was one man who pretty much created modern Florida it was Henry Flagler. Flagler (1830-1913) made a fortune in the oil business and was one of the world’s richest men when he embarked on a second career that transformed Florida from a semitropical wilderness into a powerhouse of tourism and real estate development.

The Gilded Age magnate first visited Florida in 1878 when he wintered in Jacksonville to improve the failing health of his first wife, who died only a few years later. But he was charmed by the state’s weather, and soon smelled opportunity amid the orange blossoms. Frustrated by the lack of good accommodations and transportation, in 1885 Flagler began work on the lavish 540-room Ponce de Leon Hotel in St. Augustine, then bought two railroads and formed a new company that would become Florida East Coast Railway — the predecessor to Brightline.

Flagler spent the next quarter century enticing northern tourists to visit Florida by plowing money into railroads, resorts, a steamship line, land companies, newspapers and cities along the state’s east coast from Jacksonville to Key West. “He was building transit-oriented development 100 years before the term was used,” said Jim Kovalsky, president of Florida East Coast Railway Society, a group of fans devoted to the history the railroad.

Beginning in 1892, Flagler obtained a grant from the state of Florida awarding him 8,000 acres per mile for extending his line south of Daytona, allowing new cities like New Smyrna, Titusville and West Palm Beach to develop. In April 1896, the railroad reached Miami, then home to only a few hundred souls, and as he had in other places he built streets, water and power systems, a resort hotel, schools, churches and houses for workers. He drained canals from the Everglades that covered much of the land and Miami soon had the first of many real estate booms. In 1905, he began his last and least successful endeavor to extend the railroad over open water to Key West, an ill-advised effort to capitalize on increased trade brought by the opening of the Panama Canal. Hundreds of men died during the construction of “Flagler’s Folly,” which was completed a year before Flagler died in 1913. In 1935, a category 5 Labor Day hurricane — still the most powerful storm to strike Florida — mangled the Overseas Railway and the company sold its infrastructure to the state and Monroe County, which built a highway over the old route.

In the ensuing years, as U.S. rail travel suffered a death at the hands of the automobile, Florida East Coast discontinued passenger service. Flagler’s old company fell in and out of bankruptcy but chugged along as a real estate development and freight rail enterprise. In 2007, New York-based private equity firm Fortress Investment Group paid $3.5 billion for the company with a strategy of reaping money from the railroad’s old assets. Fortress sold Florida East Coast Railway for $2.1 billion to Grupo Mexico but retained its similarly named parent, Florida East Coast Industries, and exclusive rights to run passenger service over the tracks.

Launched in 2018, Brightline represents the first privately funded major U.S. intercity passenger rail service in over a century. It projects in 2025 it will capture 4.3 million U.S. and international rail passengers traveling between South Florida and Orlando, according to a statement for a $770 million bond offering. Brightline also plans to expand to Tampa with stops at the Orange County Convention Center and near theme parks.

In an interview on CNBC, Fortress co-founder Wes Edens, a part-owner of the NBA’s Milwaukee Bucks, said Brightline’s niche is to exploit major city pairs roughly 250 miles apart. A sister firm, Brightline West, plans a $12 billion high-speed train to link Los Angeles and Las Vegas. Count Edens among the fans of Flagler. He reportedly read “Last Train to Paradise: Henry Flagler and the Spectacular Rise and Fall of the Railroad that Crossed an Ocean,” an account of Flagler and his railroad. “I found it compelling on many levels, not the least of which was that he was doing something that nobody else had done before and doing it in a way that was profoundly impactful,” Edens told the Orlando Sentinel.