Mass Timber Primed for Wider Use?

Despite obstacles, the innovative building material is used in a growing number of projects

The father-and-son team Thomas and Keith Kovatch weren’t planning to be pioneers when they decided to construct an office building in Central Florida. Then they received a random email about a seminar on an innovative building technique known as “mass timber,” an engineered laminated wood product that some architects and builders tout as a renewable resource that can rival concrete and steel in strength. After researching the benefits of mass timber, the Kovatches decided to use the material for their 30,000-square-foot office building in Clermont, which opened in September 2020 as Florida’s first mass timber structure, according to WoodWorks, a mass timber trade association. Keith Kovatch, principal owner of the building with his father, said, “We were in the brainstorming phase and kind of stumbled onto CLT,” using the acronym for cross-laminated timber, the most widely used material in mass timber buildings. “There was no other Class A office space in the area. We’re really providing a different product.”

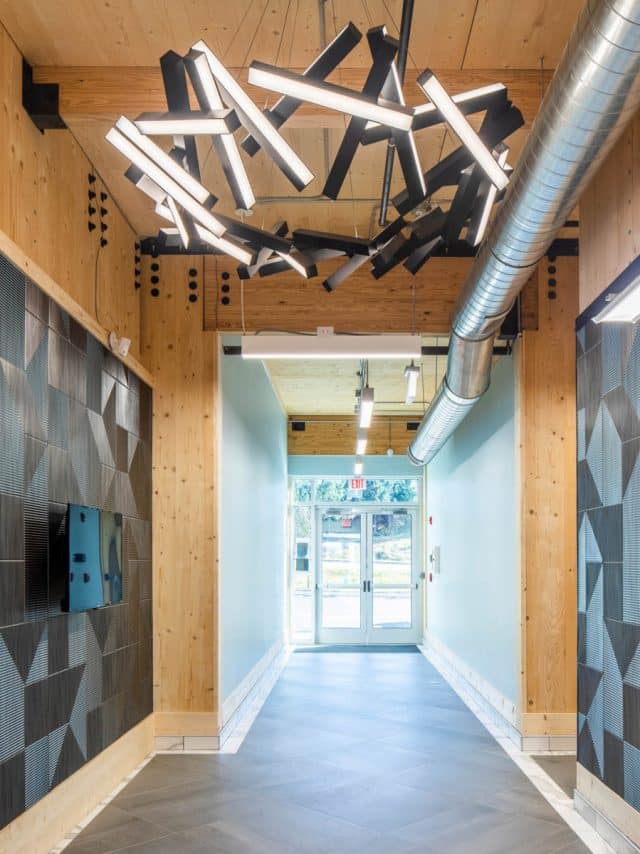

Part of an emerging trend, mass timber buildings are gaining popularity for their environmental and aesthetic appeal, as well as for being a modular construction technique that allows for the quick assembly of factory-built large wood beams, truss systems and load-bearing panels at a building site.

As of September 2022, more than 1,500 multifamily, commercial and institutional mass timber projects had been constructed or were in design across all 50 states, an increase of over 25% from the previous year, according to WoodWorks. High-profile corporations are helping lead the way. Walmart, Google and Microsoft are among the companies that are building with mass timber, according to researchers at the University of Toronto Metropolitan University. Notably, Walmart is using 1.7 million cubic feet of regionally sourced lumber in its new headquarters in Bentonville, Arkansas, which the company said would make it the largest mass timber campus project in the United States when complete in 2025.

While not exactly a hotbed for mass timber projects, the Sunshine State shows promise: 28 mass timber buildings are either built or under construction across the state — including the Kovatches’ Clermont building, a residence in Miami built by architects who specialize in mass timber, and in a project in Fort Lauderdale being developed by Hines, a major real estate developer and among the nation’s most active mass timber builders. Another mass timber building is in the planning stage on the Gainesville campus of University of Florida — potentially the latest in a wave of mass timber structures being built at institutes of higher education.

History and benefits of mass timber

CLT was developed roughly 30 years ago in Austria and Germany after builders perfected a method to make panels by adhering three to seven or more timber layers together and applying high compression, according to various research reports. These mass timber panels can be built in large dimensions up to 60 feet long and 20 inches thick at off-site factories and delivered for rapid assembly at a construction site.

“Construction work may take as little as three to four months for buildings of up to nine stories, a fraction of the time contrasted with traditional construction techniques, for example, concrete,” according to an analysis cited in a 2021 research report in the Journal of Building Engineering.

Depending on the project, mass timber is marginally more expensive than traditional building techniques, according to various research studies, though some developers claim they have saved money because of the faster construction times and reduced labor.

But many advocates and developers say saving money is not their primary goal for using mass timber, and they tout other pluses, including the beauty of natural exposed wood and mass timber’s environmental benefits. Building with mass timber instead of traditional building materials can help companies reach commitments to design carbon-neutral buildings. (See story on ESG on page 6.) Unlike concrete and steel, trees absorb carbon dioxide and release oxygen, effectively helping to mitigate climate change, according to studies cited by University of Washington researchers in a 2022 article published in the academic journal Sustainability.

“In fact, these buildings are far more environmentally sustainable than any other building typology in the world,” Steve Luthman, senior managing director at Hines, said in a real estate podcast on CBRE’s website.

Challenges: sourcing, building and fire codes

Despite its benefits and an upward trend in its use, mass timber projects face an array of obstacles. These include limited supply of mass timber products in many parts of the country, questions over its fire resistance and the slow adoption of mass timber in local building codes.

When it comes to sourcing, the Northwest — principally the states of Oregon and Washington as well as British Columbia, Canada — has the strongest market for mass timber. The region contains a vast supply of spruce and pine trees suitable for mass timber projects and a high concentration of CLT production facilities, said Judith Sheine, a professor at the University of Oregon’s School of Architecture and Environment. She noted that building officials in the Northwest have more experience and knowledge of mass timber projects — and customers and developers are more aware of the construction technique.

Florida and other states in the Southeast have pluses, notably an extensive acreage of Southern yellow pine timberlands suitable to produce wood for mass timber projects, experts said. According to the latest figures from the U.S. Forest Service, Florida has 14.9 million acres of publicly and privately owned timberland, which are lands potentially available for the growth and harvest of trees for commercial purposes.

But the region lacks infrastructure. The Southeast has only one CLT manufacturing facility, in Dothan, Alabama.

Questions over building and fire codes also limit more widespread adoption of mass timber. Building codes require structures meet the same requirements for safety and performance regardless of the material. Ricky McLain, a senior technical advisor with WoodWorks, said dozens of fire tests on CLT and other types of mass timber materials conducted by various labs have consistently shown that mass timber buildings have very good fire performance. “Mass timber products have inherent resistance to fire because they char on the exposed perimeter surfaces while retaining strength, slowing combustion and allowing ample time to evacuate the building,” he said.

Such results have helped spur updates to some building codes, including to the 2021 International Building Code that permits “tall” mass timber buildings up to 18 stories that meet stricter requirements, including fire-resistance ratings. But most state building codes haven’t caught up, making it potentially more cumbersome for builders to get approval from local building officials on a case-by-case basis. “The Florida Building Code doesn’t include a provision for mass timber,” said Mo Madani, a technical director of the Florida Building Commission. A technical advisory committee voted to not include the IBC update in the 2023 revision of the state’s code. But there is a side door: The code allows local jurisdictions to approve projects that use “alternative materials, design and methods” provided these at least match the “quality, strength, effectiveness, fire resistance, durability and safety” of traditional methods.

Sheine said, “we can expect it to take two to three years [for jurisdictions] to adopt new IBC regulations, while Oregon was the first in the Northwest to adopt the new code regulations.”

Florida projects

Despite the challenges, developers are moving forward with projects. Perhaps the first mass timber house in Florida was completed in January 2022 in Miami’s Coconut Grove neighborhood by architects Chris and Shawna Meyers, both of whom teach at the University of Miami School of Architecture. Dubbed House in a Garden, the Meyers built the single story, 1,800-square-foot home to highlight wood’s natural beauty — what mass timber advocates call “biophilic feel.” The home uses CLT manufactured with Florida-sourced Southern yellow pine. It took eight months to get approval from Miami-Dade County and the city of Miami building officials before construction could begin. Shawna Meyer said this was no longer, and perhaps shorter, than constructing a traditional home in Miami, which she attributed to a public-private partnership and collaboration between the architects’ firm Atelier Mey and a lab at the University of Miami’s School of Architecture. A wrinkle in the process was gaining special approval to use the novel building material in a high velocity hurricane zone. The Meyers were required to provide the results of resiliency and impact testing to prove that CLT met these higher building standards. “There was definitely a learning curve for the city, and many meetings going back and forth,” she said.

Among the most high-profile projects in Florida is a six-story, 180,000-square-foot office building being developed by Hines in Fort Lauderdale’s Flagler Village neighborhood. It is one of four buildings in a mixed-use project scheduled for completion in 2025, Hines spokesperson Madison Przywara said. The project is the latest of roughly two dozen mass timber projects the Houston-based developer has built or is developing worldwide since it completed its first in 2016 in Minneapolis’ North Loop neighborhood. The 221,000-square-foot mass timber building is being leased by tenants that include Amazon and Industrious, a company that provides coworking office space.

Hines embraced using mass timber after it noticed commercial tenants increasingly rented office space in converted old brick and timber warehouses in downtown areas of cities like San Francisco, Chicago and Brooklyn. Tenants love the cool vintage look, with exposed brick, timber beams and bow truss roofs. But the retention rates were low because, in the end, tenants wanted more modern amenities. This led Hines to create a business unit named T3 — standing for Timber, Transit and Technology — to develop “brand new old buildings,” Luthman said. Hines’ Fort Lauderdale mass timber project will include a rooftop deck, private tenant outdoor balconies, shared conference and work spaces, a fitness center and enhanced Wi-Fi connectivity.

Heavy timber is not a gimmick for us

“We are currently considering timber buildings in several other Florida markets,” said Pryzwara, who noted Hines can “demand premium rents” in completed projects so far. “Heavy timber is not a gimmick for us, but it is a proved effective way to balance responsible and sustainable development with occupier needs and desires.”

Cost analysis

There’s a debate over whether mass timber is cost competitive with other materials, such as concrete and steel. In a study published in the Journal of Building Engineering, researchers at Oregon State University’s School of Civil and Construction Engineering conducted a cost analysis that found mass timber was 6.4% more expensive than concrete in the construction of an 18-story residential building.

Despite such reports, there are exceptions. The Kovatches said they saved about 35% on their Clermont office over using traditional building materials and techniques. Time and labor costs were substantially lower, Keith Kovatch said. This was despite the longer learning curve for the general contractor and engineers who were unfamiliar with building using mass timber. “It took us about three months to get the CLT structure erected once the slab was poured, but in all likelihood for our building it probably could be done in as little as six weeks with an experienced crew,” he said. Supporters say the costs of using mass timber may decrease in the years ahead as the suppliers catch up with demand and developers, tenants and building officials become more familiar with the innovative building technique.

Universities embrace mass timber

It appears cost is not the primary driver for institutions of higher education, which have increasingly embraced mass timber, particularly for use in natural resource learning spaces where scholars focus on the renewable aspects of wood. Mass timber-made buildings have popped up on numerous campuses, ranging from North Carolina State’s Plant Science Building to Oregon State’s Oregon Forest Science Complex, a teaching and collaborative-learning space in Corvallis, Oregon.

At the University of Florida in Gainesville, the Meyers, the Miami architects, have been hired to scope out a proposed $80 million academic building made of mass timber. The Integrated Natural Resources building would bring together three academic natural resource programs and related centers that are scattered across campus, said Scott Sager, an assistant director and forester in the School of Forest, Fisheries, & Geomatics Sciences. Sager is a member of a team that recently received a $500,000 grant from the U.S. Forest Service to, among other things, refine the project and compare the environmental impacts of using mass timber versus traditional construction techniques. The team is seeking support from donors for the proposed 200,000-square-foot building, which Sager said will take several years to build and design after the funds are raised.

Sager said a benefit of using modular building techniques is the shorter on-site construction time, which would reduce the disruption to UF’s busy campus. He also noted that mass timber is an ideal material to house academic programs devoted to natural resource research and development. “It is fitting to create a teaching tool that is made of an environmentally sustainable product that grows back and produces clean water and air while storing carbon dioxide,” he said.

Undoubtedly heavy timber has less of a carbon impact than using concrete or steel, agreed Keith Kovatch. But he said this was a “side benefit” in the Kovatches’ decision to use mass timber in their office building. “It wasn’t necessarily at the forefront of our minds,” he said. “It might be a selling point for others.”