Debate over rent controls heats up in Florida

Florida has emerged as a surprising battleground over rent control this year as local governments look for ways to manage escalating housing costs. Elected officials in a handful of cities and counties across the Sunshine State have seriously debated the controversial issue in response to increasing demands from residents who face some of the steepest rent hikes in the country.

This is the first time the issue has popped up in a significant way in Florida since 1977, when the state Legislature passed a law that effectively invalidated a rent control ordinance in the city of Miami Beach by setting a high bar for local governments to implement them. For nearly half a century, state law only permits local elected officials to set price controls on rents after declaring a “housing emergency which is so grave as to constitute a serious menace to the general public,” and back it up with evidence. Rent controls also require voter approval, expire after only one year, and cannot apply to single-family homes, tourist units or luxury apartments.

Despite the hurdles, in August the Orange County Commission narrowly voted to place a “rent stabilization ordinance” on the Nov. 8 ballot after declaring a local housing emergency. The proposed law would set a maximum rent cap on multiunit buildings equal to the annual increase in the consumer price index (CPI) for urban consumers in the South, which stood at 9.8% in June.

The Florida Apartment Association and the Florida Association of Realtors quickly filed suit seeking an injunction to invalidate the ballot initiative, saying it violates state law because the situation doesn’t amount to a housing emergency. Nevertheless, Florida Circuit Judge Jeffrey Ashton denied the request to block the issue from the ballot, despite his own reservations about whether it met state law and would hold up to future legal challenges. Elected representatives “determined that it is in the best interest of those citizens to place a matter before them that is, in this Court’s opinion, contrary to established law,” he wrote. Yet “the public interest is rarely served by removing [a] contentious issue from public debate.”

U.S. rent controls started more than a century ago

Rent controls began in the United States in the early 20th century with New York’s adoption of tenement and tenant rights laws, Ashton wrote, citing historical precedents. At that time a governmental committee found unprecedented evictions, unreasonable and extortionate increases in rent, and multiple families crowding into apartments designed for one resulting in “insanitary, disease, immorality, discomfort and widespread social discontent.” A second wave of demands for rent controls came during the Great Recession and World War II. In 1942, Congress passed the Emergency Price Control Act to fix maximum prices and rents and directed a price administrator to establish fair and equitable prices. The act expired in mid-1947.

Today, roughly 200 jurisdictions have some form of rent controls — oftentimes pegged in some way to the inflation rate. These include the states of California and Oregon, and municipalities such as New York; Portland, Maine; St. Paul, Minnesota; San Francisco; Camden, New Jersey, and Washington, D.C., according to the National Multifamily Housing Council. In contrast, an interactive map on the council’s website shows that more than half of states preempt local jurisdictions from implementing rent controls.

Despite including Florida among states with preemptions, the multifamily housing group labels the state a “true hotbed” in the skirmish. This comes at a time experts say Florida faces a housing shortage during one of the fastest-growing periods in state history. Last year, rents soared an average of 20% or more in every major Florida market, from Jacksonville to West Palm Beach, according to CBRE Econometrics Advisors. (Figure 1)

Figure 1 – Source: CBRE Econometric Advisors

Florida proposals

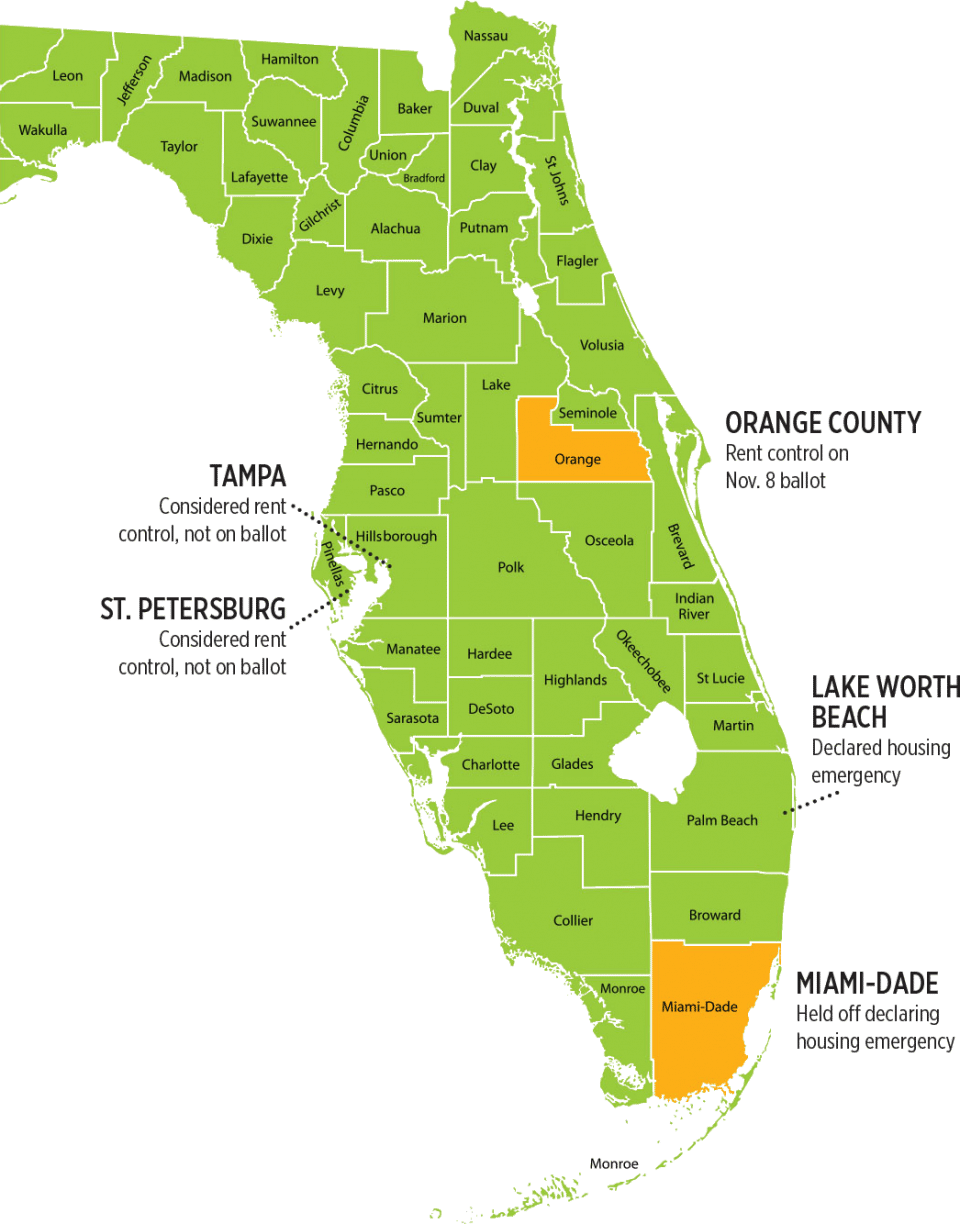

This summer, proposals to declare housing emergencies and explore rent controls showed up on the agenda not only in Orange County but in Tampa, St. Petersburg, Miami-Dade County and Lake Worth Beach. (Figure 2) City councils in Tampa and St. Petersburg — after multiple public meetings to consider rent controls — ended up voting against placing a referendum on the November ballot, citing, among other things, the potential for costly legal challenges. In Miami-Dade County, where rents have reportedly topped traditionally high-rent cities of New York and San Francisco, commissioners approved an ordinance requiring that tenants receive 60 days’ notice of rent hikes of 5% or more. But a commissioner withdrew his proposal to study whether the county faced a housing emergency. In Lake Worth Beach, commissioners declared a housing emergency and issued a call for a study to research alternatives, including rent controls. “The rent control thing is a possibility,” Mayor Betty Resch said in an email. “I am not convinced it’s the best way to go. But [we] need a lot of information.”

Florida Communities with Rent Control on Public Agendas in 2022

Orange County cited various reasons for pushing ahead with its proposed ordinance. These included a 25% increase in Orlando-area rents during 2021, an increase in evictions, a shortage of as many as 26,500 housing units countywide and a 5.2% vacancy rate for rental properties, which it said was the lowest since at least 2000. (Figure 3) At a four-hour public meeting in August, Orange County commissioners heard personal appeals from about 60 people — ranging from concerned landlords to rent-stressed tenants — before voting 4-3 to place the referendum on the ballot. Orange County Commissioner Emily Bonilla, who proposed the rent control initiative, wrote in a post on Facebook: “If the industry really wants to help, like they said they do, then the first thing they could do is stop raising rents — that would really help out.”

| Year | Inventory | Occupancy | Asking Rent | Y-O-Y % Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 132,080 | 94.8% | $1,697 | 25.0% |

| 2020 | 126,059 | 90.9% | $1,357 | -2.0% |

| 2019 | 121,425 | 97.9% | $1,384 | 2.2% |

| 2018 | 115,887 | 92.8% | $1,353 | 3.5% |

| 2017 | 110,132 | 94.6% | $1,308 | 5.8% |

| 2016 | 105,534 | 94.1% | $1,237 | 3.8% |

| 2015 | 102,718 | 93.8% | $7,191 | 5.7% |

| 2014 | 98,779 | 93.9% | $1,127 | 3.2% |

| 2013 | 94,890 | 92.8% | $1,092 | 3.0% |

| 2012 | 91,647 | 93.7% | $1,061 | 2.4% |

| 2011 | 91,349 | 92.2% | $1,035 | 1.7% |

| 2010 | 90,929 | 91.4% | $1,018 | 0.3% |

Sources: CoStar, GAI Consultants

Notes: (1) Excludes units classified as affordable under various state or federal guidelines and already subject to rent controls and/or income restrictions; (b) units in the vacation and/or military market segments; (c) residential condominiums and co-ops.

Figure 3

But critics of the measure said it would do little to help renters in the long run. In fact, a key part of the landlords’ case against Orange County came directly from a consultant’s report that the county commissioned that indicated the rental market fell short of the statutory requirement needed to impose controls. GAI Consultants concluded that rent controls could cause more problems by discouraging the construction of apartments and other housing. “At the end of the day we don’t believe there is an emergency and the benefits, if any, associated with rental controls are offset by unintended negative consequences,” the study’s co-author Owen Beitsch told Due Diligence.

Moreover, Beitsch said “it’s doubtful” that the measure would have a meaningful impact because, depending on how the ordinance is interpreted and enforced, it would apply to as few as 5,000 to 12,900 renter-occupied units in a county with 230,000 units. There is also a danger that if approved the ordinance could dampen housing construction by sending a “signal” to prospective developers and apartment owners to avoid the market or raise rents now before rent controls are established, he said.

At least one leading builder already has declared his company won’t build more apartments in the county if voters approve the measure. “Camden will not build in a rent-control market,” Ric Campo, chief executive of Camden Property Trust, told the Wall Street Journal. The Houston-based developer and landlord owns 4,000 units in Orlando.

Amanda White, director of governmental affairs for the Florida Apartment Association, cited three main contributors to the housing crunch across the state: intense population growth, a slowing of new housing construction and high construction costs. These components create a perfect environment for rising rental rates and less affordable housing. But imposing rent controls would disrupt the market and further slow the development of new housing. “Local governments are looking for a quick fix,” she said. “A real solution would be to build more housing, but this is not a quick fix in the same way that rent control [might be].”

Rent controls in San Francisco and Cambridge, Mass.

Academic researchers have studied the effect of rent controls in various cities and regions for many years. This research indicates the effectiveness of the policies are “mixed at best,” GAI reported, and it noted the programs are complex and involve an extensive administrative structure to manage.

One prime example is San Francisco, which expanded its existing rent controls in 1994. In a paper published in the American Economic Review in 2019, researchers found that the new rent controls reduced the city’s supply of rental housing by 15% from 1994 to 2016 because landlords increasingly converted buildings to condos or redeveloped them so they were exempt from the price controls. Also, they found that on average people who lived in rent-controlled units were 10% to 20% more likely to remain in their homes relative to a control group. “Thus, while rent controls prevented displacement of incumbent renters in the short run, the lost rental housing supply likely drove up market rents in the long run, ultimately undermining the goals of the law,” the authors concluded.

Another closely examined market is Massachusetts, which functions as a laboratory for researchers to study before-and-after effects of rent controls. In November 1994, state residents voted to outlaw rent controls after they were in place for many years in cities such as Cambridge, which had imposed rent controls on residential properties in 1970. By 1994, price-controlled units typically rented for 25% to 40% less than nearby uncontrolled units, a clear benefit to tenants in those units. But valuations were significantly lower than noncontrolled units, and maintenance and amenities were often subpar as their owners spent less on repairs, upkeep and capital improvements.

In a 2014 study published in the Journal of Political Economy, researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the National Bureau of Economic Research estimated that abolishing rent controls added about $1.8 billion to the value of Cambridge’s housing stock between 1994 and 2004, nearly a quarter of Cambridge’s total residential price appreciation in this period. Not surprisingly, removing rent controls resulted in steep rent increases and a sharp rise in residential turnover. Meanwhile, Cambridge experienced an overall “investment boom,” as investments in housing units, as measured by building-permit filings, more than doubled on an annual basis over the next several years. The removal of rental controls resulted in increased maintenance, upgrades to local amenities and “potentially more efficient sorting of consumers to housing.” All this “spurred overall gains in neighborhood desirability,” the authors wrote.

A shift in St. Paul

In more recent years, several U.S. cities have adopted rent controls in response to fast-escalating rents and a shortage of affordable housing.

One is St. Paul, where residents voted in November 2021 to impose a rent-control ordinance that some have called the most stringent of its kind in the nation. The ordinance capped annual rent increases at 3%, not tied to inflation, and it does not exempt new construction nor allow landlords to raise rents by more than 3% when a tenant moves out.

Since then, construction has plummeted citywide even though a local housing committee said the city is short 11,000 units from what it needs. In one highly publicized case, Ryan Cos., a Minneapolis-based master developer, halted a mixed-used project to redevelop a 122-acre site on a bluff overlooking the Mississippi River. The development, on land that once housed a Ford Motor Co. plant, is slated for 3,800 rental units, but only 320 have been completed, according to Axios Twin Cities. St. Paul officials responded in September by reworking its rent control measure to exempt newly constructed housing from the 3% rent cap for 20 years. One housing advocate complained Ryan Cos. is using the pause in construction as leverage against the community. The company hasn’t said when or whether it will continue the project.

Meanwhile, in Orange County, the rent control debate is on a pause, too, as the question is now up to the county’s electorate. Will they vote to impose rent controls for the first time in Florida in 45 years — and challenge the high hurdle set by the state law? Florida renters, policymakers and landlords are closely watching.