Big print job

On average it took more than 10 months to build a house in the United States in 2023, nearly three months longer than in 2015, according to government data. Economists and other experts blame the homebuilding sector’s poor productivity on culprits including stringent regulations and a shortage of skilled labor.

But they also cite another factor sometimes overlooked: The sector’s slow adoption of new innovations, which even the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) acknowledges has been holding the industry back.

Now a group of startups and homebuilders are trying to rewrite this narrative by harnessing three-dimensional concrete printing (3DCP), a technology advocates say could revolutionize home building. Picture giant robots and automation techniques producing homes faster, cheaper and more safely than conventional methods. University research studies suggest concrete printed homes are stronger, have higher energy efficiency ratings and provide better resistance to fire, floods and high winds than conventionally built houses. Using precisely measured concrete material to print walls also can yield a smaller environmental footprint because there is little waste and no need for formworks that end up in landfills.

“We can’t keep doing the same thing we’ve been doing for the last 50 years and expect different results,” said Tim Stark, the owner of BeSpoke of Montana, a building and remodeling company in Billings. He is morphing his company to exclusively build concrete-printed homes.

Three-dimensional printing technology has long moved beyond hobbyists’ desktops to factory floors, where it’s now used to make everything from car parts to prosthetic limbs. The late Harvard business professor Clayton Christenson, who coined the term “disruptive technology,” considered 3D printing a classic disruptor because it is simpler, cheaper and more convenient than traditional manufacturing technology. In a 2024 report entitled, “Delivering on Construction Productivity is No Longer Optional,” the consulting firm McKinsey & Co. said 3D printing could help the sector “climb out of its productivity rut.”

The concept of giant automated house-building machines has become so irresistible that almost any 3DCP project is guaranteed to attract widespread attention. Consider the crowds that flocked to witness Florida’s first 3D-printed house. So many people wanted to see it the builder set up an online reservation system to manage tours. “We had schools visiting and professors coming from all around,” said James Light, the homebuilder who hired a 3DCP company to print the walls. “It was just kind of a spectacle, honestly.”

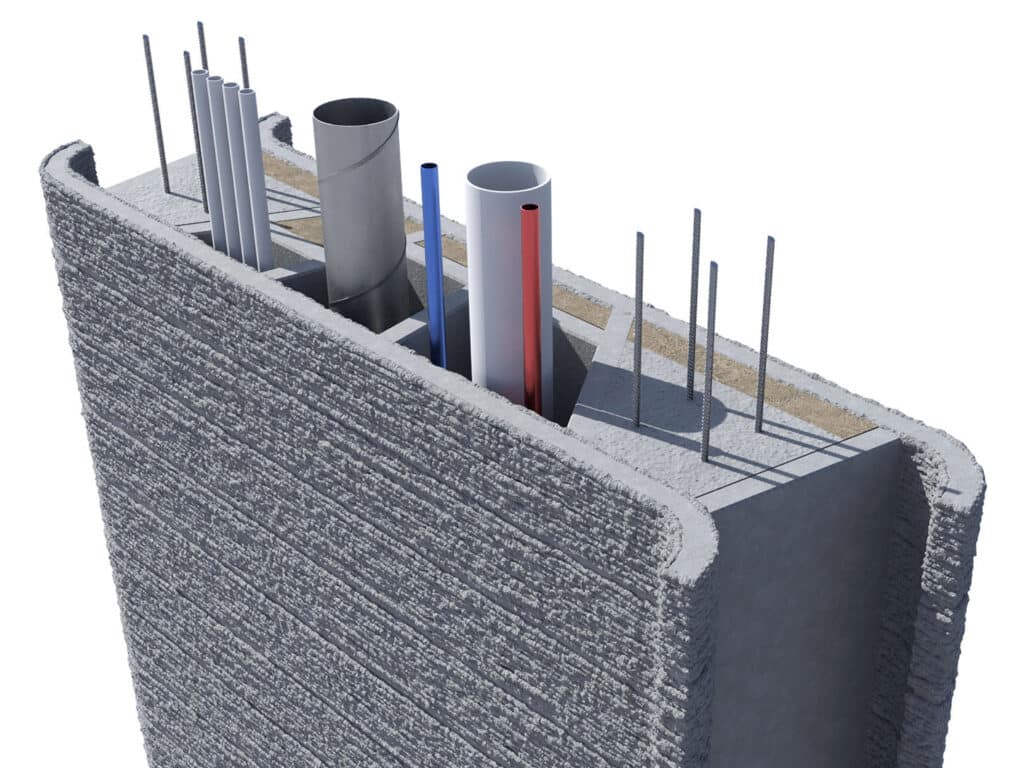

Cross section of 3D concrete printed wall:

- 3D-printed exterior / interior walls

- Mechanical, electricity, plumbing

- Insulation option

- Lightweight concrete (insulation material)

- Vertical / horizontal reinforcement as required by house design

To try to untangle hype from reality, we spent three months gathering information from researchers, homebuilders, developers and technology companies to learn about 3DCP and understand the potential and challenges. We called and emailed companies that announced 3DCP projects in recent years to find out if they were indeed completed and if there was evidence printing was quicker or saved money than conventional builds.

Below we provide our account, but if you want the bottom line: Contrary to what’s been reported, the technology is not always faster or less expensive than traditional construction. Even so, it’s probably unwise to write it off. Most any supposed disruptive technology must run a marathon and 3DCP has only just left the starting gate.

First, some history

The technology may seem new, but 3D concrete printing goes back about 85 years, said Chaofeng Wang, an assistant professor in the University of Florida’s School of Construction Management, who studies the technology. Printing with concrete started in late 1930s when William Urschel, an Indiana investor and contractor, created a machine that extruded layers of concrete to build walls.

But nothing much happened until the mid-1990s when an engineering professor at the University of Southern California invented the earliest version of today’s computer-based robotic system to “print” concrete following a digital design. Behrokh Khoshnevis said the idea came to him when he was repairing cracks in the wall of his living room after the 1994 Northridge, California earthquake. A few years later he gained widespread attention for printing a 500-square-foot structure inside a lab, and he gave a TEDx talk and interviews in which he predicted the technology would transform the way we build houses at a fraction of the cost.

All these years later it seems the number of news stories and press releases vastly exceed the number of 3D printed buildings. In a paper recently published in the journal Buildings, researchers from Germany’s Technical University of Braunschweig identified 356 3D printed buildings constructed worldwide since 2013. Nearly half were built in 2024 (Figure 1), suggesting 3DCP may be gaining traction. But it’s hardly a drop in the ocean when you consider 948,000 single-family homes were built in the United States in 2024, according to the Census Bureau.

Source: A Global Snapshot of 3D-Printed Buildings

Most 3D-printed buildings built so far are residences, but others include offices, storage facilities and exhibits. The majority have been built in the United States, followed by China, Europe and the Middle East, such as Dubai, which aims to become a global leader with a goal of using 3DCP for one-quarter of all new buildings in 2030.

According to various research studies and industry claims, 3DCP may save roughly 20% to 30% on the cost of building a house. Advocates say 3DCP allows as few as two or three workers to erect the walls, including one to use a handheld computer to ensure printing goes according to plan and another to manage concrete mixing and delivery. That’s far fewer than the array of workers — typically hard-to-find subcontractors — that builders rely on to frame a conventional stick-built house. But reported savings are difficult to quantify without real cost data, which is closely guarded and not readily available. Certainly, such estimates raise questions when you consider the cost of framing a house with interior and exterior walls, dry wall and other elements that 3DCP would replace make up roughly 20% of the cost of a new house, according to our review of NAHB data. Most costs are for foundations, roofs, doors, windows, and electrical and plumbing systems that are added the traditional way by construction workers. Austin-based startup Icon, which built the first U.S. permitted 3D-printed home in 2018 for reportedly $10,000, seems to have begun tamping down expectations of huge cost savings. The company announced last year it is taking orders for projects starting at $25 per square foot for wall systems, which it said was lower than the cost of conventional wall systems based on data from the NAHB. Icon claimed this would represent a savings of up to $25,000 for the average American home.

How it’s done

Really big printers are either mounted to a massive gantry crane or a mobile robot with long-reaching arms. A software program feeds a design to the printer, which follows the outline and squirts out a fancy concrete mixture layer by layer from the bottom up. The finished 3D-printed structure has been described as looking like everything from corduroy to the folds of a shar pei dog. Many of the entrepreneurial homebuilders we spoke with said they were mesmerized by watching YouTube videos of computer-programmed nozzles twisting and turning to layer perfectly shaped walls. It’s almost like watching a robot pastry chef frost a cake or an oversized soft-serve ice cream dispenser. The system can also easily print distinctive curved buildings that are more aesthetically appealing than conventional box-shaped houses.

Often underappreciated is the precise mix of binding cement, water, aggregate and additives needed for a successful build. To the layman, it looks like regular concrete but it’s more a special sauce. The mixture needs to be liquid enough to move through the nozzle and not clog and set up quickly so by the time the printer head comes back around it’s solidified enough to accept the next layer without collapsing. Materials react differently under varying weather conditions. “You can’t go to Lowe’s and get a bag of Sakrete,” said Nathan Metz, a Lima, Ohio real estate investor who joined forces with local homebuilder John Smoll to build two 3DCP houses. They recently purchased their own 3D printer and plan to ramp up production. “You have to have the right mixture.”

Tim Lankau, founder of Hive3D, a Houston 3DCP company that was finishing its ninth house as we wrote this story, considers the concrete mix more important than the big machines laying it down. “The technology to move a nozzle around in 3D space is not innovative at this point,” he said, adding his company is trying to jerry-rig their own system using off-the-shelf industrial robots. But projects can run into delays and quality problems if the materials aren’t just right and optimized for the setting. Lankau’s company now uses a special mix that replaces cement with fly ash, a material left over from coal-burning power plants and industrial facilities, supplied by a Utah company.

Rex Rizk spoke by cell phone from a construction site in Shiner, Texas where his company was printing its first three homes. Employees with Germany-based PERI 3D Construction were training Rizk and several employees to use a gantry-style 3DCP system made by Denmark-based COBOD. Rizk said among the big challenges was understanding the curing process, getting the finicky concrete mixture just right and ensuring the print nozzle didn’t vibrate during the printing. “The learning curve is pretty steep and it’s definitely a trial by fire,” he said.

Local and state building codes can also pose a hurdle. Unlike traditional wood-frame and cement-block construction, which are well-defined in local building codes, printing concrete walls is considered an “alternative means and methods” in the International Building Code, and many states and local jurisdictions are slow to approve 3DCP projects. “The key challenges to adopting 3D-printing broadly are scaling the technology to meet demand and securing municipal approval to use the technologies in various jurisdictions,” said Brad Conlon, senior vice president of development for D.R. Horton, the largest U.S. homebuilder.

Large bets

Despite such obstacles, D.R. Horton is among a cadre of major investors, homebuilders, and global concrete suppliers and equipment makers plowing billions of dollars into the 3DCP ecosystem. Icon, the biggest and most well-known 3DCP company, has raised $451 million in multiple rounds of funding and is reportedly valued at $2 billion. Icon has printed homes for the chronically homeless in Austin and poor families in Mexico. It also was awarded $57.2 million from NASA to develop a 3D construction system for use on the moon or Mars.

Icon’s most closely watched earthly project is what’s billed as the world’s largest 3D-printed neighborhood — 100 single-family homes in Georgetown, Texas, about 30 miles north of Austin. The company recently completed printing the houses in a partnership with Lennar, which finished each home using conventional methods. Lennar, the second-largest U.S. homebuilder, isn’t saying whether it made money or if it plans more 3D-printed homes, said spokesperson Danielle Tocco. So far, they’ve reportedly sold half of the houses in the neighborhood, called Wolf Ranch, at prices in the mid-$400,000 to $500,000 range.

This spring D.R. Horton plans to begin testing a wall system printed by another company, Melbourne-based Apis Cor. Conlon said this first project is dependent on Apis Cor obtaining approval from the International Code Council, an organization that sets standards for building safety and efficiency. He confirmed D.R. Horton has made an investment of an undisclosed amount in Apis Cor, as well as Icon, and it is investing in other “transformative products and technologies,” Conlon said. These include Bamcore, which makes bamboo-based structural building components, and Boxabl, which makes foldable, modular homes.

In the 3DCP market, Icon and Apis Cor are among hundreds of companies trying to hone operations and win business. They have many different approaches. While Icon and Apis Cor don’t sell their pricey machines — they serve as printer contractors — other manufacturers sell theirs and train builders to assemble and operate them. Some homebuilders are testing the waters by adding the technology to their box of tools, while others are brave enough to put all their chips in to focus only on 3DCP.

Survey of 3DCP projects

Illustrating the fraught world of startups, we followed up on more than a dozen 3DCP projects announced in recent years and found many were never built or suffered substantial delays or other problems. For example, in November 2022, the founder of a Tampa startup named Click, Print Home said in TV and newspaper interviews the company was building the city’s first 3D-printed house near MacDill Air Force Base. Construction seems to have never started. The CEO did not explain in an email why it wasn’t built.

Many projects fall in the trial-and-error category. Alquist 3D, a startup that has successfully printed six buildings, including an 8,000-square-foot expansion of a Walmart Supercenter in Athens, Tenn. In the summer of 2023, Alquist printed Iowa’s first 3D-printed house but by Thanksgiving the structure was torn down after it began cracking and didn’t meet a strength test. Alquist founder Zachary Mannheimer said, “It was a loss as Alquist removed the structure at our own cost, but the insights gained were worth more.” Since then, the company relocated its headquarters to Greeley, Colo., lured by local and state tax breaks and grants, and partnered with a local community college to create a training program to bring workers into the industry. Mannheimer conceded the costs for 3D-printed houses are higher today than, say, building with cement blocks. “However, as a matrix is built out determining the right material ratios based on time of year and climate, prints will increase in speed and efficiency, which will inevitably drop cost,” he said.

Jim Ritter, the founder of Florida startup Printed Farms and the printing subcontractor for Florida’s first house, agreed that 3DCP doesn’t cut costs, at least not yet. “Right now, we are not cheaper than block,” he said, though they are less expensive to heat and cool because 3D-printed structures are better insulated and have higher R-values. In June 2023, Printed Farms completed the “world’s largest 3D-printed building,” a 10,100-square-foot horse barn and circle-shaped horse training structure in Wellington, Fla. The facility sold for $3.8 million to a Cincinnati chiropractor and his wife who show horses. Ritter said the appeal of 3DCP for the contractor is “machines don’t need such a large pool of labor, and their costs are easier to control. As the new generation of machines makes printing easier and faster you will see a shift to 3D-printed shells. Right now, we are not there.”

Many projects are aimed at addressing affordable housing issues, though it’s hard to see much cost savings so far. On Dec. 6, 2024, about 150 news reporters and community and elected officials flocked to a site in Melbourne, Fla., to watch a robot begin printing a 1,300-square-foot home for Space Coast Habitat for Humanity, with funding from Wells Fargo Bank and the city of Melbourne. When we followed up in February, the printing was weeks behind schedule, said Anna Terry, executive director of the affordable-home building organization. The house is being built on land it already owned, will cost roughly $250,000, about the same as a similar home built with conventional methods, she acknowledged. Terry was optimistic the job would be completed soon after the robotic printer was relocated to its fourth and final printing position. “When you’re pioneering something it’s not as quick as you think,” she said.

The most notable recent project we learned of is Zuri Gardens in south Houston, which would be the nation’s second-largest 3D-printed neighborhood, with 80 homes priced in the $200,000s. It is being developed by Cole Klein Builders of Houston with houses printed by Hive3D. The partners’ proposal to use 3DCP was selected recently by the city of Houston through a competitive bidding process. The city is kicking in $1.8 million in affordable housing funds. “Otherwise, we couldn’t do it,” said Harry Klein, cofounder of Cole Klein Builders. Construction was slated to begin in 60 to 90 days.

Big finish

Circling back to Khoshnevis, the pioneering USC engineer, we found he isn’t as optimistic as he once was about 3DCP. He ticked off reasons the technology hasn’t made much impact, including high costs of specialized materials and printing machines, maintenance, training of skilled labor, and slow-evolving building regulations. “This technology is not going to take over pretty fast and in my opinion may never meet the expectations that the hype has created,” he said.

We would be amiss if we didn’t check with James Light, whose company Gulf Coast Additive Manufacturing & Design was behind that first 3D-printed Florida home. The three-bedroom, 1,400-square-foot house sold for $230,000 in 2023. It took 26 hours to print the walls, but this stretched nine days because of various delays. He didn’t like the aesthetics, so Light covered the printed walls with stucco and as a result the house lacks distinctive ribbed walls. Light admitted his company lost perhaps $40,000, despite benefiting from a low-interest loan provided by the city of Tallahassee. Undeterred, Light built another house, in Inlet Beach, Fla., using a different technology. But he was dissatisfied with the equipment and service from CyBe Construction, the Netherlands-based manufacturer, so he finished it with cinder block after printing just one-third of the walls. Still, Light remains upbeat, and he has moved to a third project, this time using a truck-mounted robotic-arm printer made by Germany-based Putzmeister. A major supplier of concrete service trucks and pumps, Putzmeister recently established its 3D-printing operations in Miami. They are planning to print a 16-foot-tall boat storage facility in Navarre, Fla., starting this spring. Light said 3DCP is like any other new technology. “It’s going to crawl before it can walk … and then,” he said hopefully, “it’s going to sprint.”

As Christensen explains in his book, “The Innovator’s Dilemma,” disruptive technology may often have early performance problems or may not immediately have a proven practical application. It may take several iterations before the technology works out problems and its rate of improvement exceeds existing technology. Brian Potter, a structural engineer who follows the 3D-printing construction industry, wrote on Substack: “The important thing for building 3D printing isn’t the current state” but where it is on the curve of a classic disruptive innovation. “Unfortunately, figuring this out is difficult.”

By this yardstick, we won’t know for a while whether 3DCP will make us wildly more efficient homebuilders. Check back in a few years. It has just entered the race.

Charles Boisseau is editor of Due Diligence.

Related stories

For the media

Looking for an expert or have an inquiry?

Submit your news

Contact us

Follow us on social

@ufwarrington | #BusinessGators