Thirty-six-million-acre balancing act

Long ago, Mark Twain supposedly said, “Buy land, they’re not making it anymore.” The witticism seems ever more apt today, particularly in Florida, where the state’s strong population growth and competition for land is drawing increased attention from academics, public officials and landowners.

Researchers at the University of Florida’s Center for Landscape Conservation Planning inventoried Florida’s land and forecast how its use may change over two separate time periods — by 2040 and by 2070. The research suggests that if population and development trends continue Florida could lose 400,000 acres of agricultural lands by 2040 and 2 million acres by 2070.

The UF study highlights the delicate balancing act Florida faces to provide enough places for people to work and live while also sustaining agriculture and natural resources. The project was created in partnership with 1000 Friends of Florida, a nonprofit land conservation advocacy organization whose members include scientists, public officials, large landowners and land-use attorneys. They want to draw attention to how Florida can best make use of its 36 million acres in an era of rising sea levels, a continued drop in agricultural land and the need for new residential and commercial projects.

Acknowledging that development and conservation interests may often oppose each other, research team members stressed the project is not anti-development. “There is the potential for an article to be doom and gloom, that this [loss of agricultural and natural lands] is coming and there’s little we can do about it,” said Thomas Hoctor, director of UF Center for Landscape Conservation Planning. “That’s not the point of our project. Our point is this could happen if we don’t get our act together to protect the state’s agricultural lands.” Scientists say these lands provide not only food but many vital “ecosystem services,” including wildlife habitat, wetlands protection, water storage and filtration.

We chose to explore the nearer-term study that looks at how Florida’s acreage is carved up today and how it may change by 2040.

The lay of Florida’s land today — and perhaps tomorrow

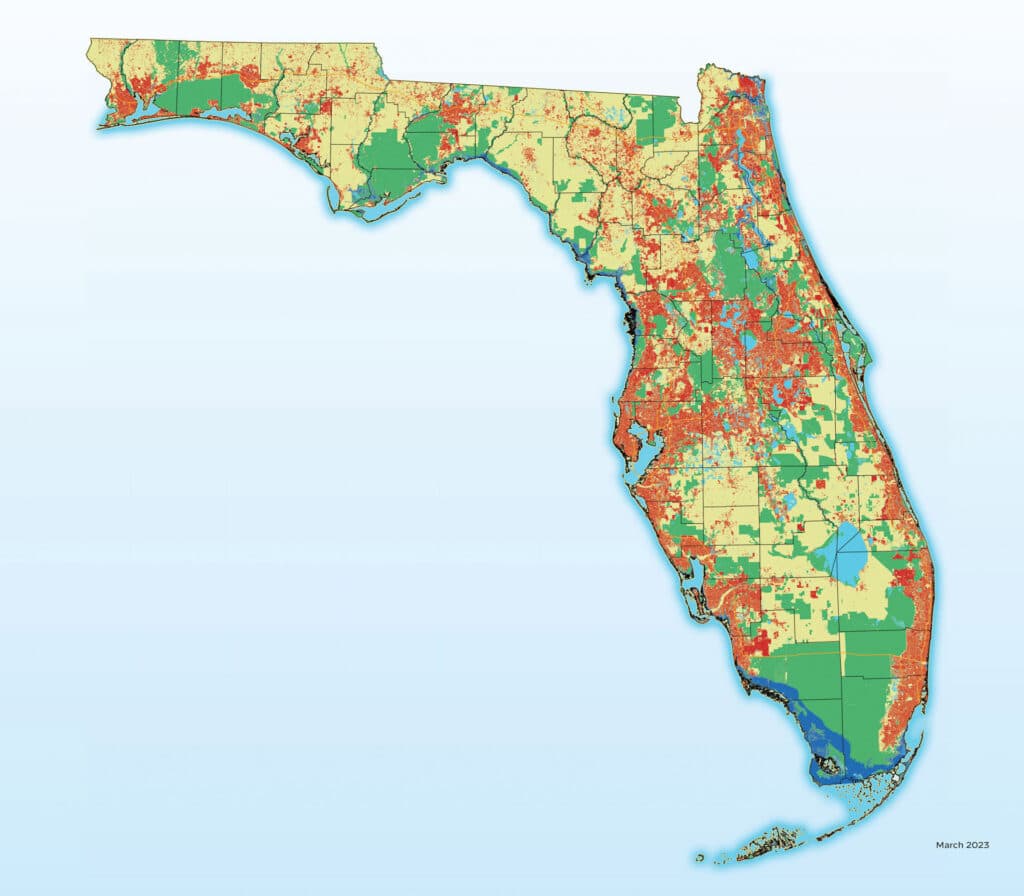

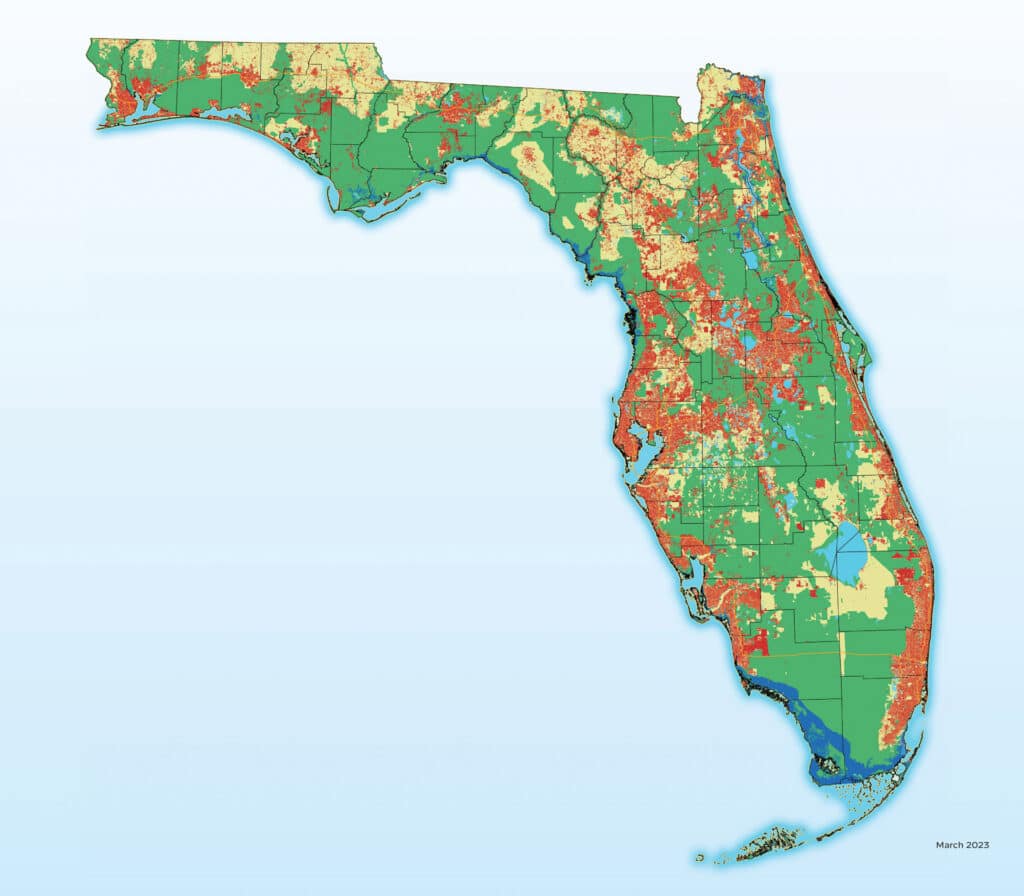

Florida’s land is divided into four primary categories: agriculture, natural, developed and a catch-all “other” category. The researchers outlined two scenarios for how this usage may change in the years ahead: one labeled “sprawl” and one “conservation.” Below we provide an overview of the land use today and the study’s 2040 forecasts. (See Figure 4 for more details.) The sidebar titled “Assumptions” shows the assumptions researchers used in their projections.

Agriculture: Roughly 20% of Florida’s 36 million acres is devoted to agriculture based on 2020 data used in the study. About 6.4 million acres are for traditional or “unprotected” agriculture, with vast acreage devoted to citrus, fresh market vegetables and cattle production. This reflects how Florida continues to rank among the top agricultural and cattle-producing states despite large areas converted to residential and commercial development in recent decades. About 2% — 856,000 acres — is “protected” agriculture, meaning this land is off limits to development. By 2040, the study’s sprawl forecast shows traditional agriculture will fall to 6 million acres but it would decline far more — to 3.75 million acres — under the conservation scenario. While this may seem counterintuitive, it reflects a major shift of agricultural lands going from unprotected to protected status.

Development: About 15%, or 5.4 million acres, is developed, including everything from residential rooftops and shopping centers to parking lots and utilities. By 2040, in the sprawl forecast, Florida’s developed land would increase another 946,000 acres to 17.5%; under the conservation scenario it would increase 674,000 acres to 16.8%.

Natural conservation lands: About 10 million acres, or 27%, of Florida is natural conservation areas, such as lands protected by national, state, local and private programs. Under the sprawl scenario, the acreage would fall to 9 million, or 24.8%, because of rising sea levels. But it would increase to 14 million, or 39%, under the conservation forecast. The conservation scenario assumes the same population growth and sea-level rise but assumes much more natural land will go undeveloped — in part because of incentives provided by the state of Florida — and new development would be 30% more compact.

Other: Open water (lakes, rivers and creeks) makes up 5% of acreage and an “other” category comprises nearly one-third. Researchers said this includes areas devoted to timber, mining, “unprotected” natural areas and miscellaneous uses. By 2040, this category would decline slightly under the sprawl scenario, with some possibly inundated by rising seas, but fall nearly in half under the conservation forecast as the use of these lands shift.

Maps in Figures 1, 2 and 3 provide a visualization of how land use may change in the next two decades. (For simplicity, the maps combine some categories; for example, the yellow-colored areas encompass unprotected agriculture, open water and “other” uses.) UF researchers said they know that neither the sprawl nor the conservation forecast will prove precisely correct. Rather “the goal is to provide a basis of discussion for debating what the future will look like,” said Michael Volk, assistant director of the UF Center for Landscape Conservation and Planning.

Florida Forever and Florida Wildlife Corridor

Notably, while the researchers foresee a continued decline in agriculture land, their conservation scenario anticipates a spike in the transfer of property to protected status that may also allow for farming and ranching. This in large part reflects the anticipation of the continued expansion of two state conservation programs that have gained widespread bipartisan support.

First is Florida Forever, a conservation and recreation lands acquisition program created by the state Legislature to protect natural habitats and water resources, provide coastal resiliency, and restore and maintain public lands. Florida has spent roughly $3.3 billion to purchase more than 900,000 acres since the program’s inception in 2001, according to the state Department of Environmental Protection, and recently committed $100 million in recurring annual funding to the program.

Second is the Florida Wildlife Corridor Act,which the state Legislature passed unanimously in 2021. The law’s stated purpose is “to create incentives for conservation and sustainable development while sustaining and conserving the green infrastructure that is the foundation of Florida’s economy and quality of life.” It dedicated $300 million specifically to create a wildlife path that would encompass 18 million uninterrupted acres stretching from Everglades National Park and the Florida Panther National Wildlife Refuge in South Florida to Osceola National Forest in the north. Researchers say the idea is science-based: The long-term survival of many Florida species — including imperiled black bears, red-cockaded woodpeckers and Florida panthers — is dependent upon their ability to move across the landscape, unimpeded by development, traffic and other potentially damaging obstacles. Panthers, the official state animal, serve as the charismatic poster child and a driving force for this conservation effort. The endangered animals, on the brink of extinction in the 1970s, now number roughly 200. “Panthers have always been a key foundation of the corridor,” Hoctor has said.

The Florida Forever priority list includes 128 projects up for purchase by the state, containing more than 2.1 million acres with an estimated value of $7.8 billion. The properties are ranked using a scoring system based on their ecological benefits. Ninety-nine of the projects overlap with the Florida Wildlife Corridor. In one of its latest purchases, Florida agreed to pay $141 million to preserve six properties totaling 64,444 acres stretching from the Panhandle to Southwest Florida. This included $78 million to buy 17,229 acres of ranchland from Alico, a land manager and one of the largest citrus producers in the U.S. (The Fort Myers-based company, originally known as Atlantic Land and Improvement Co., was once led by the late Ben Hill Griffin Jr., a citrus pioneer and UF benefactor.) The Hendry County property is in what is known as the Devil’s Garden Florida Forever project, and will contribute to the expansion of the adjacent Okaloacoochee Slough State Forest, a core territory for the panther and a path north from the Everglades, according to the nonprofit Florida Wildlife Corridor Foundation.

Despite state support, however, the UF forecast anticipates chunks of the wildlife corridor will be developed in the years ahead. This isn’t surprising given that roughly 40% of the wildlife pathway is in private hands and there is no requirement that landowners ensure it’s not developed. At the current pace, it would take decades for the state to purchase and conserve the targeted lands, according to a 2024 state assessment of Florida land conservation.

Figure 4 – Comparison of Florida 2040 development scenarios

| Type of Use | Baseline | % of Total Acres | Sprawl 2040 | % of Total Acres | Conservation 2040 | % of Total Acres |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Developed | 5,428,000 | 14.94 | 6,374,000 | 17.54 | 6,102,000 | 16.79 |

| Protected Natural Land | 9,850,000 | 27.11 | 8,997,000 | 24.76 | 14,076,000 | 38.74 |

| Protected Agriculture | 856,000 | 2.36 | 854,000 | 2.35 | 3,236,000 | 8.91 |

| Traditional Agriculture | 6,418,000 | 17.66 | 6,022,000 | 16.57 | 3,751,000 | 10.32 |

| Other* | 11,778,000 | 32.41 | 11,028,000 | 30.35 | 6,110,000 | 16.81 |

| 2019 Open Water (i.e., lakes, rivers) | 2,006,000 | 5.52 | 2,006,000 | 5.52 | 2,006,000 | 5.52 |

| Sea Level Inundation: Protected Lands | 0 | 0 | 854,000 | 2.35 | 928,000 | 2.55 |

| Sea Level Inundation: All Other Land Uses | 0 | 0 | 201,000 | 0.55 | 127,000 | 0.35 |

| Total Acres | 36,337,000 | 100 | 36,337,000 | 100 | 36,337,000 | 100 |

*Includes timberlands, mining lands and other miscellaneous land uses not classified as agriculture, developed, protected, protected agriculture or open water.

Sources: UF Center for Landscape Conservation Planning, 1000 Friends of Florida

Competing needs

It’s easy to extol the benefits of land conservation, but preservation efforts also raise many important considerations that policymakers must wrestle with — beyond the obvious of how to pay for and maintain the land. The state land conservation report highlighted some unresolved issues, including: “How much conservation land is needed and for what purpose?” “Should the current pace of the state’s conservation land acquisition efforts be accelerated?” And, “at what point does the volume of conservation land acreage alter the pattern of economic growth as expanding metropolitan areas are forced upward instead of outward?”

Indeed, every week seems to bring news of a development group seeking regulatory approvals to convert heretofore rural property to hundreds or even thousands of homes, commercial projects and roadways. Such ambitious proposals have sparked opposition, highlighting perhaps the biggest challenge builders face: gaining public support. This is going on at the same time the state faces a competing priority of addressing an acute housing shortage, which is exacerbated by a scarcity of developable land. Stuart Miller, co-CEO of Miami-based Lennar Corp., one of the nation’s largest homebuilders, touched on the thorny issue in a quarterly earnings call last year. “We believe that the new supply of homes will be limited as developed land is scarce and increasingly more expensive to develop,” he said. “This will continue to limit available inventory and maintain supply/demand imbalance.”

Conservation easements

An important aspect of Florida’s land future is not only the outright purchase of properties for preservation but also obtaining properties via conservation easements. This is a mechanism that allows a landowner to sell their developmental rights in exchange for continuing to use the property for agriculture, timber production, outdoor recreation and similar uses. The easements are perpetual and attached to the deed. Most of these transactions are less-than-fee simple, meaning the interest in the property is acquired at below market value to keep the land in private ownership.

Rural land experts say conservation easements have become the most cost-effective way to keep land in as natural state as possible. Scores of rural property owners are willing to sell their development rights for easements, but they await the availability of funding, said land broker Dean Saunders. He runs Saunders Ralston Dantzler Real Estate, one of Florida’s largest rural land brokerage firms. In the past two years Saunders’ firm has brokered 35,000 acres of conservation easement transactions totaling $101 million, including in fast-growing counties Polk, St. Lucie and Osceola.

One recent example is the state’s purchase of a conservation easement on 4,808 acres in an area north of Tallahassee called the Red Hills Conservation project. In addition to allowing the owners, Gem Land Co., to continue ranching and farming, the agreement allows the building of eight single-family homes, some outbuildings and driveways. The $8.25 million for the easement came from the Florida Family Lands Protection program, a sister of the Florida Forever program that funds conservation easements.

The state isn’t the only entity buying working farms and ranches for conservation purposes. Federal and regional agencies, including local water districts, and nonprofit environmental organizations are in the mix. A major player is the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Resources Conservation Service. One example: It partnered with nonprofit National Fish and Wildlife Foundation to pay $4.28 million for the conservation easement on 1,700 acres of Blackbeard’s Ranch in Manatee County. The land buffers Myakka River State Park and is touted as providing a potential range for Florida panthers to expand north of the Caloosahatchee River.

Jim Strickland, who has been in the cattle business since childhood, manages the cow-calf operation. He also serves as co-chair of a “climate smart” working group of agricultural and forestry leaders that supports agriculture and promotes scientific research of rural lands’ ecological benefits and use of new technologies, such as invisible fences to allow wildlife to travel across ranchlands. The group was created by the nonprofit Solutions From the Land in collaboration with UF’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. Strickland knows the monetary value of agricultural lands. He is a former county appraiser. “I’ve seen hundreds and hundreds of thousands of acres go from agricultural to residential development,” he said, noting he sold some of his own property to developers over the years. “I’m not the guy going to stand alongside of the road saying no more development.”

Strickland often guides other ranchers who grapple over whether to conserve or sell their property. They share stories about ranching life and how they may pass cherished land to the next generation. But Strickland couldn’t put a price on one of his latest stories. It came early one morning in April while he was riding his horse near the boundary of the Myakka River State Park. He caught a “four-second glimpse” of a rare animal he had never seen before. “I am 69 and I’ve been in the woods from the Everglades to the Georgia line my entire life,” he said. “And, I saw my first panther.”

Charles Boisseau is editor of Due Diligence.

Related stories

For the media

Looking for an expert or have an inquiry?

Submit your news

Contact us

Follow us on social

@ufwarrington | #BusinessGators