Flooding the zone

Regulators and emergency officials are increasingly urging people to take flooding more seriously. Strengthen properties against flooding, don’t build in high-risk flood zones and buy flood insurance to protect your home. They argue not nearly enough homeowners buy flood insurance, especially in an era when climate scientists have documented rising sea levels and higher global temperatures, which tend to make storms wetter and more intense.

But they are having trouble getting their message to stick. Just 5% of U.S. homeowners carry flood insurance, and the rate is slipping. The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), which underwrites most U.S. flood insurance policies, covered 4.66 million properties as of May, down from 5 million in 2021. “Flood risk is probably the fastest-growing risk in the nation — and the least insured,” said Craig Fugate, who served as the administrator of FEMA during the Obama administration and lives in Gainesville.

The most recent examples of devastating floods came when two major hurricanes made landfall on Florida’s Gulf Coast in less than two weeks. In late September, Helene broke storm surge records and inundated properties from Tampa Bay to Florida’s Big Bend; the damage stretched hundreds of miles inland to Georgia, Tennessee and the Carolinas, where unprecedented flooding killed more than 230 people. Then, on Oct. 9, Milton landed near Sarasota, spawned numerous tornadoes and flooded communities across the peninsula.

Many homeowners find out the hard way that their standard property insurance policy — which cover hurricanes, wildfires and most other natural disasters — excludes coverage for flooding, which accounts for 90% of the damage from all natural disasters in the United States, according to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). To cover flooding, homeowners must buy a separate policy, typically from the taxpayer-backed NFIP.

Tim Cerio, CEO of Citizens Property Insurance Corp., Florida’s state-owned insurer of last resort, emphasized the importance of buying flood insurance when he spoke in September at the UF Bergstrom Real Estate Center’s annual board retreat. “What people don’t realize is if a hurricane causes flooding from storm surge and your house is flooded that’s not covered by your hurricane policy,” he said. “That’s a flood event, and you’re not going to get a penny if you don’t have flood insurance.”

Several unrelated factors are now converging to reshape the flood insurance market, particularly in Florida, one of the nation’s most flood-prone states. First, NFIP, which has long failed to collect enough premiums to sustain itself, has rolled out a new pricing formula designed to better match prices with risk. Also, newly configured flood maps are putting more Florida properties in high-risk flood zones. Finally, a new state law is requiring Citizens’ policyholders to buy flood insurance regardless of whether they live in a risky area. All this may start to change the flood insurance calculus in Florida. In the past two years, as the number of people nationwide who bought flood insurance dipped, the percentage of Florida homeowners with flood policies has ticked up, and now account for 37% of all NFIP customers nationwide (Figure 1).

Source: National Flood Insurance Program

To grasp what’s going on, we spoke with insurance and local floodplain experts, examined NFIP’s new pricing model and reviewed reconfigured flood maps in many Florida coastal counties. The bottom line: More homeowners must purchase flood insurance — particularly in Florida — and they’ll pay much more than in the past.

First, the background on NFIP

The roots of today’s flood insurance market go back to 1968 when Congress created the NFIP after most private insurance companies abandoned the market because of the unpredictable and catastrophic damage caused by floods. The federal program largely paid its own way until 2005, when the catastrophic Hurricane Katrina inundated New Orleans resulting in the NFIP’s debt soaring to $16.9 billion. Then hurricanes Sandy in 2012 and Harvey in 2017 sent the debt spiraling upward. The program owes the U.S. Treasury $20.5 billion, despite Congress canceling $16 billion of its debt in 2018 (Figure 2).

Major storms:

- August-October 2005: Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, Wilma

- October 2012: Hurricane Sandy

- August-September 2017: Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, Maria

*In 2018, $16 billion of debt was canceled rather than repaid.

Sources: Congressional Research Service, General Accounting Office

This is the back story for the new pricing model FEMA recently introduced to shore up its finances to increase rates to better match the risk of flooding. It’s the biggest change in the way flood insurance premiums are calculated since the inception of NFIP — and a response to criticism that taxpayers were funding big payouts on coastal properties in risky locations. Going back to 1978 and through mid-2024, just 50 U.S. counties and parishes have accounted for 73% of the $80 billion in claims paid by the NFIP, with more than half in Texas, Louisiana and Florida, according to our review of NFIP data. Previously, NFIP set rates largely based on a property’s elevation in high-risk zones delineated on Flood Insurance Rate Maps, or FIRMs. This outdated model no longer accurately reflected the true flooding risk, and critics said cheap insurance encouraged people to buy properties in flood-prone areas. Called Risk Rating 2.0, the new approach to set actuarially fair rates has increased premiums because it accounts for more variables. “These include flood frequency, multiple flood types — river overflow, storm surge, coastal erosion and heavy rainfall — and distance to a water source along with property characteristics such as elevation and the cost to rebuild,” a FEMA spokesperson told us. Using new-generation tools and models, “FEMA now has an actuarially sound rating approach that is equitable, reflects a single property’s individual flood risk and is designed to adapt to climate change.”

The largest rate increases are in Gulf states, which have been underpriced despite having some of the highest danger of floods. Under Risk Rating 2.0 the median price for flood coverage for a single-family home in Florida nearly doubled to $1,402 a year from $787, according to data from FEMA. Some communities will see premiums jump 300% or more, chiefly in coastal counties where nearly all properties are subject to storm surge (Figure 3). Florida counties with the steepest increases are Franklin ($5,129 for a new policy vs. $1,047 before), Monroe ($4,697 vs. $1,149) and Lee ($3,795 vs. $1,089). The ZIP code with the biggest increase: 34201 in Naples where homeowners pay $8,480 for a new flood policy vs. $1,301. Most existing homeowners get some relief because the law caps increases to 18% a year. But if you’re buying a new policy, you’ll pay the full risk-based rate immediately.

Figure 3 – Risk-based vs. current cost of flood insurance

Annual premiums for single family homes in highest-priced Florida counties; as of Aug 31, 2023

| County | Single-family home policies | Median current premium | Median risk-based premium | Inland flood* | Storm surge* | Coastal erosion* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Franklin | 1,976 | $1,047 | $5,129 | 100% | 100% | 37% |

| Monroe | 19,574 | $1,260 | $4,697 | 100% | 100% | 42% |

| Lee | 74,220 | $1,089 | $3,795 | 100% | 100% | 6% |

| Charlotte | 27,938 | $1,307 | $3,414 | 100% | 100% | 7% |

| Levy | 567 | $1,263 | $3,329 | 100% | 89% | 37% |

| Collier | 46,578 | $853 | $3,195 | 100% | 100% | 14% |

| Wakulla | 1,022 | $1,039 | $2,952 | 100% | 99% | 19% |

| Pinellas | 58,410 | $1,165 | $2,809 | 100% | 94% | 28% |

| State total and averages | 894,619 | $787 | $1,403 | 100% | 58% | 8% |

*Percentage of policies with exposure

Source: Federal Emergency Management Agency

The all-important flood maps

An essential element of the federal flood insurance program requires FEMA to regularly map the country to determine areas most vulnerable to one-in-100-year floods, areas that the FEMA deems highest risk. These are known as special flood hazard areas (SFHAs) and are delineated on the flood maps. FEMA is required to regularly reassess flood maps, but researchers have found that about two-thirds of FIRMs are out of date and don’t account for the changing environmental conditions causing flood risks to rise in many parts of the country. Nevertheless, these maps serve as the de facto source of information for a property’s flood risk and for determining whether a flood policy is required at all. Federal law mandates that the owners of properties in a SFHA to carry flood insurance if they have a government-backed mortgage. Most banks require flood insurance in these high-risk zones, too. (Homeowners who don’t have a mortgage may choose to take on the risk themselves and avoid insurance altogether.)

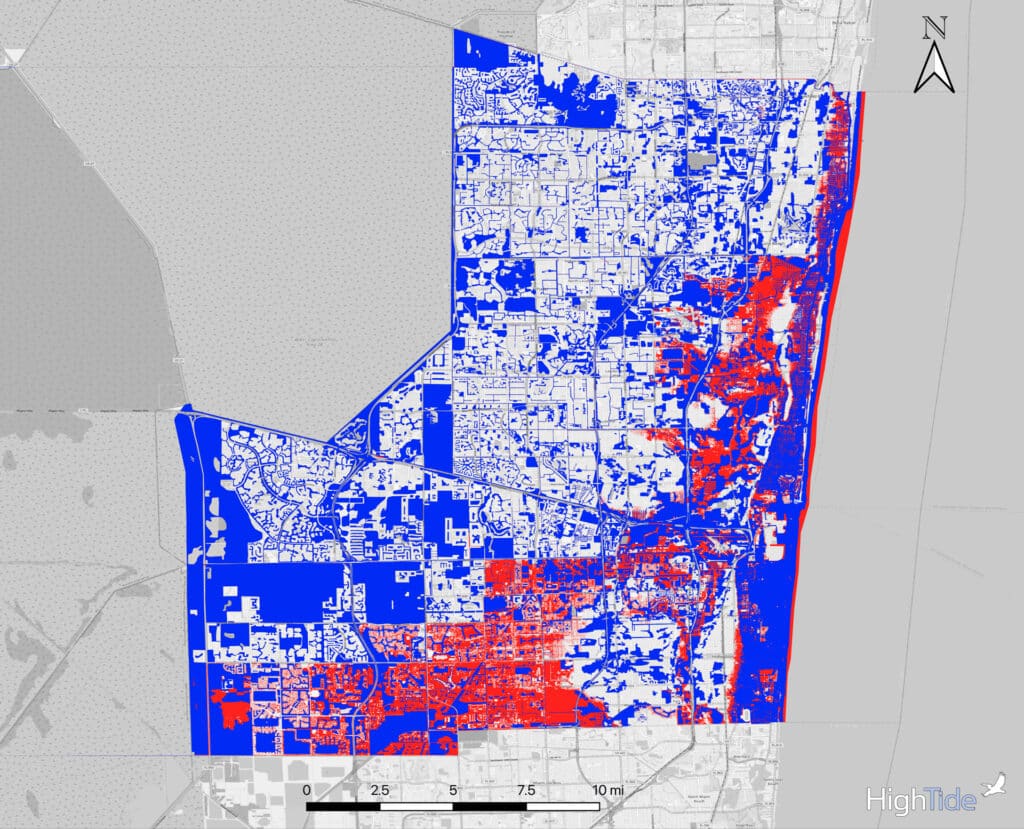

New flood maps are shifting more properties into SFHAs. Nearly 89,000 more properties in Broward County were put in a high-risk flood zone on July 31 when a new FIRM went into effect. The lion’s share of the properties are in inland Miramar and Pembroke Pines, fast-growing cities in southwestern Broward, where properties may be 10 to 15 or more miles from the Atlantic Ocean. The cities are low-lying and abut the Everglades, noted Carlos Adorisio, Broward County’s assistant director of environmental permitting and floodplain administrator.

The new maps didn’t appear out of the blue but are the culmination of a 10-year scientific and community engagement process FEMA began in 2014 to study coastal flood risk. The agency held many public meetings before issuing a revised preliminary map in 2021, illustrating the lengthy regulatory process to finalize flood maps. Communities may resist expanding designated flood zones because it adds costs and can hamper development. By law communities can appeal the new maps, which is what Pembroke Pines did. It submitted technical documentation to argue the new Broward County maps were inaccurate and erroneously placed tens of thousands of homes in SFHAs, according to Karl Kennedy, the city’s engineer and floodplain administrator. It lost the appeal. Nearby Miramar, where 25,878 more properties were included in SFHAs, decided not to appeal because of the time and cost of hiring engineering consultants and the small chance of succeeding, said Nixon Lebrun, a floodplain administrator and Miramar’s director of building planning and zoning.

Fresh flood maps in other Florida counties are also resulting in more properties in SFHAs. A new map rolled out in November 2022 in Lee County put 8,000 more buildings in high-risk zones (and moved 3,000 out). The newly effective FIRM for Palm Beach County added 5,800 net properties to SFHAs.

In Miami-Dade County, a new map would increase the properties in high-risk flood zones by 45,420. But this revised map is being contested by the county because of a bunch of issues, according to Marcia Steelman, a Miami-Dade floodplain administrator. One disagreement is a change in the “vertical datum” used to determine the elevation of points on flood maps, which the U.S. government adopted to replace the less accurate “mean sea level” that is changing because of global warming. “The bottom line is they are not converting the new map to the new datum correctly,” Steelman said. Also, the county contends many homes shouldn’t be counted in the SFHA because they are built on structural fill and are more than one foot higher than the base flood elevation (BFE) required of new construction in Florida. BFE is equal to the water surface elevation from a flood that has a 1% chance of occurring any year. Finally, FEMA didn’t properly account for extensive county investments in infrastructure to improve the handling of stormwater, she said.

Seemingly supporting the county’s case, an analysis by First Street Foundation placed tens of thousands fewer structures in SFHAs in several large Florida counties — including Miami-Dade. “The lower number in our model simply means that we find less properties at risk,” said Jeremy Porter, head of climate implications at First Street, which provides data to real-estate asset holders to manage climate risks in their portfolios. “This is generally due to the inclusion of stormwater assumptions in urban areas and the inclusion of our adaptation database which accounts for seawalls, pumps and other local adaptation projects.” (In contrast, across all of Florida’s 67 counties First Street’s model placed more structures in high-risk flood hazard areas than did FEMA.) A FEMA spokesperson said the number of structures in SFHAs in Miami-Dade will be finalized after the required appeal and comment resolution process.

All this highlights the underappreciated role played by local floodplain administrators, building officials and emergency managers when it comes to flood management. They have a necessarily symbiotic relationship with FEMA, whose mission is to help people and communities recover from natural disasters that damage or destroy property. Consider that communities can only qualify for the federal insurance program if they adopt and enforce minimum management standards set by FEMA to regulate development in floodplains. Many cities invest heavily in engineering and scientific consulting, hydrologic and hydraulic modeling, and hiring and training certified floodplain managers. Mark Hagerty, chair of the Florida Floodplain Managers Association and Fort Lauderdale’s floodplain administrator, outlined steps his city has taken to manage flooding, including from unprecedented rain “bombs,” such as one in April that dumped 18 inches of rain on parts of the city in 21 hours. Fort Lauderdale has committed to spending hundreds of millions of dollars to implement a stormwater flood prevention plan to limit flooding in vulnerable neighborhoods, including building and raising existing sea walls.

Also, Fort Lauderdale is among many U.S. cities, counties and parishes that participate in the Community Rating System (CRS), an NFIP incentive program that provides flood insurance discounts to those living in communities that adopt practices that exceed federal minimums. Residents get discounts on flood insurance ranging from 5% to 45%, depending on credits a community earns for various flood mitigation and safety measures. But what FEMA grants, FEMA may take away if a community fails to live up to its part of the bargain. FEMA has threatened to remove the price breaks enjoyed by residents of Lee County and several cities because they allegedly didn’t adequately enforce building standards in the wake of Hurricane Ian. Ian swamped Southwest Florida on Sept. 28, 2022, causing billions of dollars in losses and sparking an unprecedented surge in construction. The price breaks remain in place for now, but if deficiencies aren’t corrected the county stands to lose its 25% discount on April 1, 2025, said Chelsea Mullens, a Lee County floodplain administrator. This could collectively cost local NFIP policyholders millions of dollars a year.

The high cost of being in a high-risk flood zone

It’s clear there’s real money on the line over whether a property is in a high-risk flood zone or not. We contacted two insurance agencies to compare the cost for flood insurance on homes we identified on Federal Emergency Management Agency flood maps in three Florida cities — Miramar, Key West and Fort Myers. In each community we obtained a quote for house in a zone labeled “AE” — a high-risk area with a 1% or greater annual chance of flooding — and a comparable house in an “X” zone, which has a low-to-moderate flood risk. We made no effort to compare homes across markets. The average quotes for the AE-zone homes were 2.4 to 8.3 times those for the X-zone homes (Figure 4).

Figure 4 – Difference in flood coverage by market and flood zone

| City | Flood zone | Annual premium |

|---|---|---|

| Miramar | X | $509 |

| Miramar | AE | $1,352 |

| Key West | X | $745 |

| Key West | AE | $6,181 |

| Fort Myers | X | $2,613 |

| Fort Myers | AE | $6,356 |

AE: located in a special flood hazard area (SFHA) and at high risk for 1 in 100-year flooding event.

X: low to moderate risk.

Sources: UF Bergstrom Real Estate Center, Darr Schackow Insurance, Neptune Flood Insurance

In addition to higher insurance rates, living in a high-risk flood zone may mean a dip in the relative value of a home. A research study found that homes in Miami-Dade that were placed in a SFHA the last time FEMA updated the county’s FIRM in 2009 sold for a roughly 3% discount compared with those outside a high-risk flood zone. The researchers examined 217,222 transactions and 120,693 property designation changes. “The thing that we’ve always highlighted is very rarely do we see flooding impact property values in a net-negative fashion,” said Porter, who was on the research team that published the findings in the Journal of Risk and Financial Management in 2022. Though the homes continued to increase in value in absolute terms, there was “a slowing rate of appreciation for homes with risk versus homes without the same risk,” he said.

Flood coverage required for Citizens’ policyholders

Despite increased premiums, Florida is beginning to see a rising tide of flood insurance policyholders after a new state law went into effect that requires most Citizens policyholders to obtain flood insurance — no matter if a property is in a SFHA. This means roughly 85% of Citizens’ 1.2 million policyholders must buy a separate flood policy by Jan. 1, 2027, when the requirement is completely phased in (Figure 5). Given that nearly 20% of Florida homeowners carry flood insurance, and if we assume one-fifth of Citizens’ policyholders already have a flood policy, roughly 800,000 more Floridians will enter the flood insurance market, according to a Bergstrom Real Estate Center analysis of Citizens’ data. If this happens, Florida could account for about half of all the nation’s NFIP policies.

Figure 5 – Flood insurance requirement phase-in for citizens’ policyholders

| Single-family home dwelling category | Deadline to obtain flood policy | Citizens policies required to have flood insurance | Percentage of all citizens policies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Located in a special flood hazard area (SFHA) | July 1, 2023 | 179,901 | 15% |

| Replacement cost is $600,000 or more | Jan. 1, 2024 | 13,150 | 1% |

| Replacement cost $500K – $600K | Jan. 1, 2025 | 32,805 | 3% |

| Replacement cost $400K – $500K | Jan. 1, 2026 | 84,670 | 7% |

| Replacement cost less than $400K | Jan. 1, 2027 | 723,988 | 59% |

| Total | 1,034,514 | 85% |

Source: Citizens Property Insurance, as of Aug. 12, 2024

Advocates of the new law say more people insured by flood insurance will improve the resiliency of communities and result in faster recovery from storm damage. Also, the more people have flood insurance the less likelihood of disagreements as to whether the source of the damage from a storm was chiefly caused by wind — which is covered by traditional property insurance — or rising floodwaters, which is not, Citizens’ Cerio said. Historically, the disputes over the cause of damage can result in long delays in insurance payouts and litigation.

Cerio and other experts caution that no matter if your property is in a risky area it can still flood. FEMA statistics show that people who live outside special high-risk areas file more than 25% of flood claims nationwide. Hurricane Debby — rated as “only” a category 1 hurricane — caused torrential rainfall and flooding when it struck the Florida’s northern Gulf Coast on Aug. 5. But 78% of the properties affected by Debby were located outside of a FEMA-designated SFHA, according to an analysis by First Street. Debby was primarily a heavy rainfall event, a type of flooding FEMA flood maps have not historically been designed to capture, Porter said.

How the rising premiums and risks of flooding impact the overall real estate market long-term is unclear. Moody’s Analytics, which estimated the property damage from Hurricane Helene at up to $27 billion, wrote in a commentary that 2024 marks the third straight year Florida’s Gulf Coast has been slammed by a severe hurricane. This “reinforces growing concerns about long-term impacts,” Moody’s said. “Although climate hazards alone tend not to compel residents to move out of an area, further increases in insurance premiums might.”

In the end, as FEMA officials often say, “Where it rains, it can flood.” Fugate, the former FEMA administrator, said he is often asked by homeowners if they should buy flood insurance. “Do you live in Florida?” he asks. “If the answer is yes, you’re in a flood zone” — and you need a flood policy. Broward County’s Adorisio agreed: “Our recommendation is always to buy flood insurance.”

Charles Boisseau is editor of Due Diligence.

Related stories

For the media

Looking for an expert or have an inquiry?

Submit your news

Contact us

Follow us on social

@ufwarrington | #BusinessGators