One year after Ian

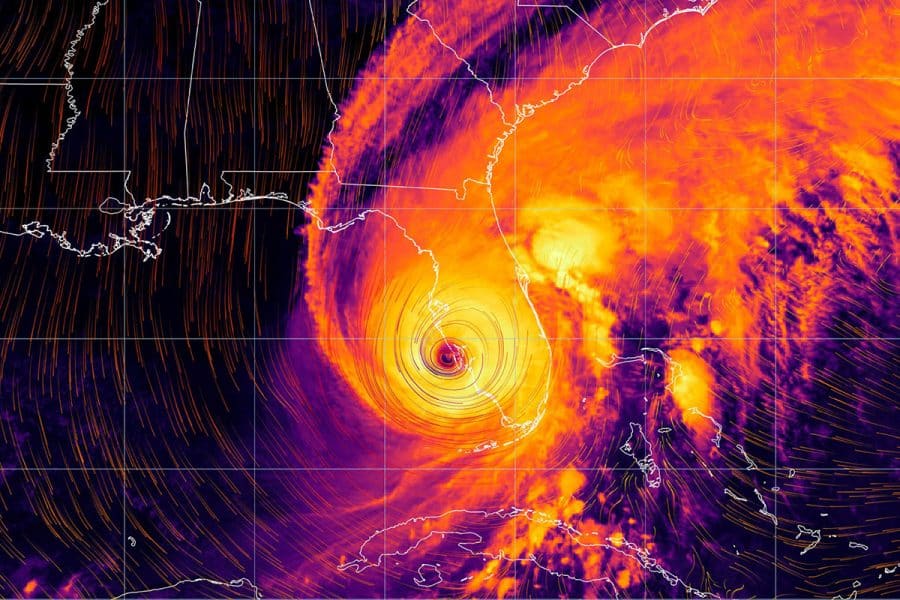

Many Southwest Florida residents had an eerie feeling in late August when yet another major hurricane with a name beginning with “I” — Idalia — rapidly intensified and zeroed in on the western coast of the state. Was it déjà vu? Less than a year earlier, even mightier Hurricane Ian barreled ashore on a Lee County barrier island packing 155 mph winds, caused $110 billion in property damage across Florida and killed 156 people. It was the costliest hurricane ever to hit Florida and the third costliest in U.S. history, according to the National Hurricane Center’s official report.

“Everybody had a little bit of PTSD,” said Fort Myers banker Greg Blurton, who was among millions of Southwest Floridians who nervously tracked the path of Idalia. You could almost hear a collective exhale as Idalia edged past and made landfall Aug. 30 in the Big Bend region, where it wrecked one of the peninsula’s least-developed coastal regions.

They weren’t so lucky 11 months earlier when Ian left swaths of Lee County looking like a scene from a post-apocalyptic TV drama. The hurricane’s high winds, catastrophic storm surge and flooding damaged 52,514 structures countywide, with 5,369 destroyed and 14,245 suffering major damage. The hurricane devastated barrier islands and areas near the Caloosahatchee River, creeks and canals. Roads and bridges were washed away; electricity and potable water unavailable for months in places; and tourism, the driver of the economy, suffered an unprecedented hit.

Even so, if anyone bet there’d be a total collapse of what had been one of the state’s hottest real estate markets they’d have lost. Certainly, property values cratered in places, most notably on the popular islands, but total values across Lee County — the state’s eighth largest — increased 11%. “It’s like a tale of two cities,” Lee County Property Appraiser Matt Caldwell said.

It appears the damage wrought by Ian serves as another example of how like most things in real estate — or meteorology for that matter — it’s all about location.

As the anniversary of the hurricane approached, we spoke with real estate experts, business operators and governmental officials to get their perspectives and learn about the challenges folks face to put things back together.

The real estate professor’s perspective

Like many residents of the Fort Myers area, Shelton Weeks and his family spent the day before Ian’s landfall putting up storm shutters and buttoning up their house. A real estate professor at Florida Gulf Coast University, Weeks’ home backs up to a canal about a quarter of a mile from the Caloosahatchee River, making it vulnerable to a major storm. He hoped the evening weather forecasts were correct in predicting Ian would continue to lean west and make landfall more than 100 miles north. But when he turned on the TV around daybreak, he saw aerial images of a perfectly formed atmospheric monster right off Fort Myers Beach. Ian had veered east. “You’ve got 15 minutes — we have to go now,” Weeks said as he hurriedly woke his wife and grown son, who had evacuated the University of South Florida’s campus in Tampa. They hightailed it for a niece’s house east of Interstate 75. The next morning, they navigated streets with downed power lines and storm debris to find the house flooded with about one and a half inches of water, a damaged roof and a mangled screened-in pool cage. “We were happy it was in as good shape as it was,” Weeks said, given hurricane-force winds pounded the neighborhood for about 12 hours. Like tens of thousands of other residents, they shifted to damage control: ripped out carpets, opened doors and windows, fired up a generator to power the fridge and electronics, deployed dehumidifiers, and took photos to document damage for the inevitable insurance claim.

As a longtime professor of real estate who has studied how floods can reshape a region, Weeks regularly makes community presentations about the local tourism-driven economy and serves as an ideal observer to assess Ian’s impact.

In the two years before Ian, Weeks said, the region’s home prices and rents ranked among the nation’s fastest increasing. They’ve since slowed. Lee County median home sales prices stood at $417,000 in July 2023, 1% lower than a year earlier when the county set a July record of $420,000 (Figure 1). It was the first time since the Great Recession in 2009 the average median sale price declined in the first seven months of a year, according to the university’s Regional Economic Research Institute. Sales of single-family homes dropped to 725 in October 2022 – the lowest monthly sales since September 2017 when Irma, another major “I” hurricane, struck Florida. But sales have begun to bounce back, with 1,106 homes sold in July, down 5% from July 2022. “I am hesitant to read too much into it,” Weeks said of the numbers. “I believe the market is still very much in flux following Ian and that what we are seeing may simply reflect noise in the data.”

Median sales prices of single-family homes and number of transactions per month countywide.

Source: Florida Gulf Coast University, based on data from Florida Realtors

On a personal level, Weeks’ storm story illustrates the experience of many homeowners whose homes suffered damage but remained inhabitable. He battled with insurance companies and struggled to find available building contractors. His primary insurer issued a check for only $780, leaving Weeks to pay roughly $30,000 out-of-pocket to replace his home’s damaged roof, gutters and soffits. He counts himself fortunate. He said he jumped in the line of a roofing contractor’s backlog of jobs only because his daughter dates the owner’s son.

Realtors’ view

Few people in the local real estate market have a longer memory than Terri Lodge, a broker at Genesis Realty who has worked in Fort Myers since 1976. She’s lived through several hurricanes, including the category 4 Charley that made landfall just west of Fort Myers in August 2004. But the destruction from Ian was so much more widespread that she wondered if this was a blow that “scares people to run from the coast,” she said.

It hasn’t happened — but with a few exceptions. Lodge and her colleague, Realtor Lillie Moroles, reported that overall demand remains steady, though it’s leveled off from what Lodge called their “rocket ride” from 2020 to 2022. In Ian’s wake, many of their clients, including seasonal residents, decided to rebuild, and some bought move-in ready homes to live in during construction. Most buyers were interested in houses not located in a flood zone and with little storm damage, though some investors bought properties with teardowns. In contrast, several clients cited hurricane danger for selling and moving, with most relocating farther inland, such as Ocala, Lakeland and Plant City. One customer living in a 55-and-older community moved after her condominium association assessed each resident $7,000 to pay for a new roof and increased monthly fees to account for higher insurance costs. “She said there was no way she could afford to go through another storm,” Moroles said.

Despite such anecdotes, the threat of storms hasn’t stopped people from wanting to live near the warm waters of the Gulf Coast. “Hurricane Ian is not deterring people to be here,” Lodge said.

On and off the islands

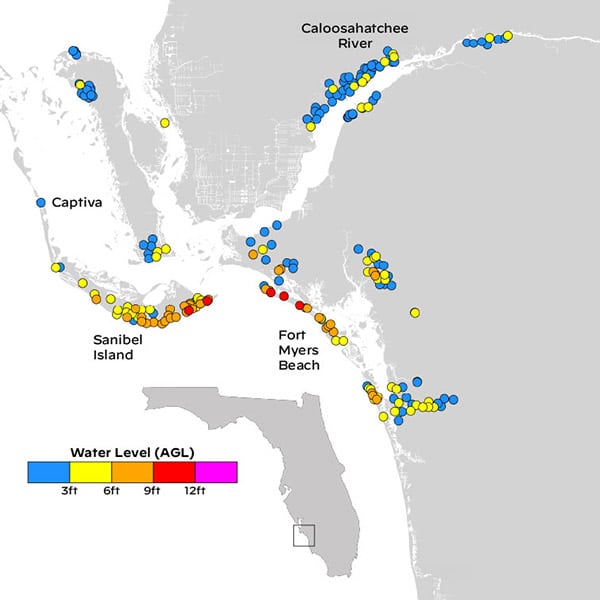

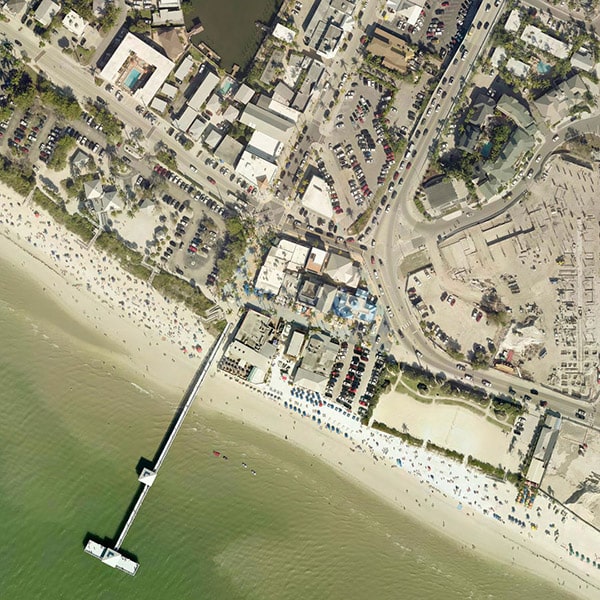

The island communities are going through the most painful transformation, said Caldwell, the county’s property appraiser. Fort Myers Beach and Sanibel, arguably the county’s biggest tourist draws, collectively saw 35% of their $11.4 billion in assessed property value vaporized (Figure 2). Nine hundred structures in the city of Fort Myers Beach alone disappeared in piles of rubble and 2,200 were damaged. Residents and visitors of the beach towns, which swell in population during busy seasons, have mourned the loss of favorite old haunts, restaurants and vintage cottages.

In contrast, Lee County’s overall total property value topped $200 billion for the first time, up 11.3%. (The table below reflects assessed values.) Two of the county’s most populous areas largely escaped serious damage: the city of Cape Coral and Lehigh Acres, known as the county’s highest point. “While the mainland is back to normal, it’s the barrier islands where you see substantial impacts that are going to take a long time to get addressed,” Caldwell said. “That’s because despite all those losses on the beach, you still had so much growth in the interior.”

Caldwell provided a post-storm aerial photo of Fort Myers Beach, which was swamped by a storm surge of up to 15 feet. Many of the buildings and homes in the area known as Times Square appear destroyed and some lots wiped clean. But the largest building appears completely intact: Margaritaville Fort Myers Beach, a 254-room resort under construction. “It is built to current codes and, like all of the properties on Fort Myers Beach built that way, it weathered the storm relatively unscathed,” Caldwell said. A resort official declined to provide information, but it was reportedly constructed with 75- to 100-foot pilings and to withstand a category 5 hurricane. “The current Florida building code works really well from my anecdotal observations,” Caldwell added. “We just struggle with the fact that so much of the building stock, particularly on the beach, was over 40 to 60 years old. There’s almost nothing left on Fort Myers Beach of the 1950s wood-frame, single-story cottages. Those got picked up and washed away and they’re gone forever.”

Figure 2 – Lee County assessed property values (in billions of dollars)

| Community | 2022 Assessed Value | 2023 Assessed Value* | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cape Coral | $26.9 | $30.3 | 13% |

| Fort Myers | $12.7 | $14.1 | 11% |

| Bonita Springs | $15.6 | $16.9 | 9% |

| Estero | $8.9 | $9.6 | 8% |

| Sanibel | $6.7 | $4.6 | -32% |

| Fort Myers Beach | $4.7 | $2.8 | -41% |

| Countywide | $131.8 | $140.3 | 6% |

Source: Lee County Property Appraiser’s Office

No matter if it’s their home or business, thousands of property owners have faced excruciating delays to hire contractors, obtain building permits and receive insurance payouts. The resolution of insurance claims has been a major factor in many decisions. Some homeowners walked away from damaged properties after receiving oft paltry checks from insurers. Many sued their insurer over denied claims, including several sources we spoke with for this article. Others who did not carry insurance just couldn’t afford to rebuild and opted to sell the land and move.

Further complicating efforts is the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s 50-50 rule, which guides rebuilding in a designated special flood hazard zone. Areas that suffered most from Ian were in these flood zones, including every inch of Fort Myers Beach, according to Weeks, who has studied the rule’s effect on rebuilding after hurricanes in Florida. The rule states any new or rebuilt structure in a special flood zone must meet Florida’s current building code, meaning the lowest floor must be at least one foot above the base flood elevation. The rule is triggered when a building official determines the cost to repair is more than 50% of a structure’s market value; if more, it’s most likely a teardown and a new one built to meet current building codes.

Weeks cited the story of a destroyed 12-unit motel in Fort Myers Beach that was purchased by new owners in June 2022. Still paying the mortgage on a valuable piece of land, the owners are on the fence about replacing the building, given the long wait for construction, financing and permitting. With the carrying costs adding up every day, Weeks said they must ask themselves: “‘Do we try to stick this out and make it to our own payday or do we take what some institutional investors are going to offer us and just wash our hands and be done?’”

Tourism economy slow to rebound

Not long ago such calculations had been far from the minds of owners of tourist-oriented businesses on Sanibel and Captiva, well-known as Florida’s best places to collect seashells. Before Ian, every one of the Sanibel Captiva Chamber of Commerce’s 540 members — from fancy hotels and resorts to eateries and bike shops — was enjoying a record year, claimed John Lai, president of the chamber. Twenty-four hours later, none of the businesses were — or could — open, he said. Not after Ian pushed up to a dozen feet of storm surge across the islands, wiped out utility services, and destroyed the bridge to the mainland. It’s been a long slog since. Only 36 of the 1,438 hotel rooms that existed before the storm in the city of Sanibel reopened as of Aug. 2 (Figure 3). In Fort Myers Beach just 26% of its 2,356 rooms reopened. Year-over-year, county tourist development taxes decreased 46.7% to $32.6 million, according to the Lee County Tourist Development Council.

It took months for the first businesses to open, and not until Jan. 2 that Sanibel officially allowed visitors. One of the first openings was Jerry’s Foods, which suffered damage inside and out but escaped the tidal surge because it was elevated 15 feet above ground level. Nowadays it seems another business opens every week. Lai said many of the challenges to recovery are the same challenges they had before Ian, notably labor shortages and escalating building costs. “But not everyone needed them all at the same time. So, the storm really just exacerbated those issues,” he said.

Figure 3 – Lee County lodging rooms reopened since Ian

| Community | Open | Closed | Total | % Reopened as of Aug. 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bonita Springs | 1,271 | 6 | 1,277 | 100% |

| Cape Coral | 820 | 0 | 820 | 100% |

| Other (Boca Grande, Lehigh Acres, Estero) | 834 | 0 | 834 | 100% |

| Fort Myers | 5,864 | 374 | 6,238 | 94% |

| North Fort Myers | 384 | 167 | 551 | 70% |

| Pine Island | 63 | 41 | 104 | 61% |

| Fort Myers Beach | 608 | 1,748 | 2,356 | 26% |

| Captiva | 144 | 440 | 584 | 25% |

| Sanibel | 36 | 1,402 | 1,438 | 3% |

| Total | 10,024 | 4,178 | 14,202 | 71% |

Even before the storm, Weeks said business operators’ biggest complaint was a high turnover of employees, who were priced out of the market as the least expensive properties were replaced by high-dollar ones built mostly by retirees and investors. “The storm was like hitting a big fast-forward button” on what he referred to as a classic gentrification trend. “We lost not only thousands of units, but we lost the most affordable units. It’s made a tight rental market here appreciably tighter.”

Ray Sandelli, commissioner of Lee County’s District 3 who represents Fort Myers Beach, said in the weeks and months after Ian the priority was getting bridges, water, electricity, roads and other essential services repaired or replaced. Removing 12 million cubic yards of storm debris was a Herculean effort. The county hired contractors from as far away as Alabama to collect, recycle and dispose mountains of demolition materials, hazardous and electronic waste, wrecked appliances, and other junk; countless washed-up or sunken boats were corralled. Even so, with parts of the county still pockmarked by storm debris and abandoned buildings, Sandelli said residents sometimes ask, “‘How come it’s not back to normal?’ Well, normal has been redefined,” he tells them, advising continued patience.

For his part, Lai said the islands may not return to normal next year, but “by 2025, we’ll be back to a critical mass of hotel rooms.”

Charles Boisseau is editor of Due Diligence.

Related stories

For the media

Looking for an expert or have an inquiry?

Submit your news

Contact us

Follow us on social

@ufwarrington | #BusinessGators