An island unto itself

Florida stands out in many ways. The peninsula has the longest coastline in the contiguous United States, the world’s largest amusement park and one of the biggest wetlands anywhere. Also, Florida is the nation’s fastest growing, with about 320,000 people moving to the Sunshine State in 2022, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

But many of these fresh arrivals are likely to discover Florida exceptionalism cuts both ways: it has the costliest and arguably most troubled residential property insurance market in the United States. Any number of measures indicate how Florida’s home-insurance business is different, but let’s start with three.

One: Average annual home-insurance premiums more than doubled the past three years to $4,231 — the highest in the nation and nearly triple the U.S. average (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Source: Insurance Information Institute, based on data from National Association of Insurance Commissioners and Florida Office of Insurance Regulation

Two: Despite the high premiums, six insurance companies were declared insolvent by regulators in 2022 (Figure 2), all before the Category 4 Hurricane Ian ravaged Southwest Florida on Sept. 28. Some insurers stopped writing new policies or abandoned the state, blaming losses on storms and high litigation and operating costs. Collectively, Florida-based insurance companies have posted negative net income five years in a row, and they lost more than $1 billion in the first nine months of 2022[1].

U.S. homeowners insurance company impairments from natural disasters, 2021-2022

Florida led the U.S. with the most insurers declared insolvent or placed in conservatorship/receivership; Louisiana was the only other state with such failures.

| Company | State of domicile | Year |

|---|---|---|

| American Capital Assurance Corp. | FL | 2021 |

| State National Fire Insurance Co. | LA | 2021 |

| Gulfstream Select Insurance Co. | LA | 2021 |

| Gulfstream Property and Casualty Insurance Co. | FL | 2021 |

| Access Home Insurance Co. | LA | 2021 |

| Avatar Property & Casualty Insurance Co. | FL | 2022 |

| St. Johns Insurance Co. | FL | 2022 |

| Lighthouse Property Insurance Corp.*, Lighthouse Excalibur Insurance Co. | LA | 2022 |

| Weston Property and Casualty | FL | 2022 |

| Southern Fidelity Insurance Co. | FL | 2022 |

| FedNat Insurance Co. | FL | 2022 |

*Wrote $58.3 million in premiums in Florida in 2020, the most recent year numbers were available.

Figure 2 – Sources: AM Best (through May 2022), Florida Insurance Guaranty Association, Florida Office of Insurance Regulation, Second Judicial Circuit Court in Leon County, Demotech

Three: With all the failures and exoduses, Citizens Property Insurance Corp. has emerged as Florida’s No. 1 home-insurance firm. At last count, it was signing up roughly 60,000 new homeowners a month because Citizens is the only company that will provide them a policy, or the only one they can afford. At yearend, the portfolio of the state’s “insurer of last resort” swelled to nearly 1.2 million policies, 15% of the overall Florida market (Figure 3), and its mounting property risk represents an exposure of $360 billion, a liability that is ultimately backed by state taxpayers.

Figure 3 – Source: Citizens Property Insurance Corp.

John Rollins (MA economics ‘97), who was Citizens’ chief risk officer 2013-2017, likens the industry’s worsening condition to a pet hamster trying to keep up with an ever-faster spinning wheel. “Eventually the hamster dies. And that’s where we are in the Florida insurance market now.”

Who knew insurance – customarily a mundane necessity of everyday life — could be so dramatic? Little wonder every major participant and influencer in the business — from regulators and politicians to insurers, lawyers and policyholders — shouted two words Floridians are practically conditioned to hear every few seasons: insurance crisis. Responding to political pressure and fears the crisis could destabilize Florida’s real estate market, legislators hurried to the state Capitol in May and again in December for separate special sessions to take a stab at fixing problems. They changed laws to try to limit excessive lawsuits by repealing the century-old “one-way” attorney fees statute covering property insurance lawsuits and fully eliminated the controversial practice known as assignment of benefits. These were legal loopholes insurers blame lawyers and contractors for exploiting to the tune of billions of dollars in frivolous lawsuits. Lawmakers also created two special funds totaling $3 billion to provide another layer of reinsurance — the essential backstop Florida’s mostly thinly capitalized insurers need to stay in business; limited the time policyholders must file claims; and chiseled away the market competitiveness of Citizens in hopes of reining in its growing policy count.

The Legislature remains largely powerless over the most obvious problem that makes the peninsula a risky place for insurers who must roll the dice every year — it is the state at the most risk for hurricanes. The trillions of dollars of ever-more valuable property crowded along Florida’s far-reaching coastline represent the largest insured loss potential in the world, according to risk modelers. But despite the ever-present danger of hurricanes, this latest crisis appears more to do with the other factors — plus perhaps the unintended consequences of past government actions and its regulatory framework — to make Florida’s market ever-more brittle, according to many long-time participants and experts of the Florida home-insurance business.

1992: Hurricane Andrew

The story of today’s complex property insurance market in Florida begins at 4:40 a.m. on Aug. 24, 1992, when mighty Hurricane Andrew barreled into Homestead, packing winds of 165 mph. Andrew destroyed more than 28,000 homes, damaged 107,000 others, and left some 180,000 people homeless. Over a grueling summer, parts of Miami-Dade County seemed post-apocalyptic — tent cities, food lines, soldiers on patrol, residents packing weapons.

Andrew spurred Florida to strengthen building codes, caused the insolvency of 11 insurers, sent insurance rates soaring and forever changed the home-insurance market. State lawmakers and regulators responded by shoring up the industry and placing a temporary moratorium on policy cancellations and nonrenewals. It created entities that still underpin the industry today, including the predecessor to what is now known as Citizens and the Florida Hurricane Catastrophe Fund (FHCF), which reimburses insurers a portion of their hurricane losses. Claims of insolvent carriers passed to the state’s Florida Insurance Guaranty Association (FIGA) to handle.

In Andrew’s aftermath, the nation’s major property insurers — such as Allstate and State Farm — have wanted less and less to do with Florida when it comes to insuring homes, especially along the coast[2]. To fill the void, Florida provided incentives to encourage a new breed of small Florida-based insurance companies, whose financial viability depends heavily on both the FHCF and the international reinsurance market. This allows them to operate without having to build up large surpluses like the major U.S. insurance companies.

Finally, Andrew spawned the Commission on Hurricane Loss Protection Methodology, which approves hurricane risk models that Florida insurers are now required to use each year to manage risk and set rates. Before Andrew, most insurers and reinsurers used simplistic premium-based methodologies to evaluate their hurricane risks, according to Karen Clark, a Boston economist who is credited with pioneering the hurricane catastrophe risk modeling industry. Clark’s clients didn’t believe her estimate that Andrew would cause $13 billion in insured losses. “They were using the model not for pricing but diversification, making sure they spread risk out,” Clark said. “Clients didn’t believe the risk was that high.” One London reinsurer bet her 5 quid that the losses wouldn’t top $6 billion. The number ended up $15 billion (in 1992 dollars), making it one of the costliest U.S. natural disasters. (See Figure 4 for list of most costly hurricanes.)

Costliest U.S. hurricanes

Estimated cost of hurricanes if they struck today, based on 2022 population and values.

| Event | main landfall spot | category | Year | Insured loss ($ in billions) |

|---|---|---|

| Great Miami | Miami | 4 | 1926 | $212 |

| Fort Lauderdale | Fort Lauderdale | 4 | 1947 | $121 |

| Lake Okeechobee | West Palm Beach | 4 | 1928 | $111 |

| Galveston | Galveston, TX | 4 | 1900 | $102 |

| Andrew | Homestead | 5 | 1992 | $98 |

| Galveston | Galveston, TX | 4 | 1915 | $72 |

| Katrina* | Port Sulphur, LA | 3 | 2005 | $71 |

| Ian | Fort Myers | 4 | 2022 | $63 |

Figure 4 – Source: Karen Clark & Co.

Wheel spins faster

The insurance market buckled again in 2004 and 2005 when eight hurricanes pounded the state, collectively causing damages that far surpassed the damage from Andrew. Several insurers went out of business, some because of mismanagement or incompetence. Citizens took over 325,000 policies from a failed insurer on a single day. Citizens and the FHCF both imposed special assessments on all insurance bills in the state to pay off billions of dollars in state debt. “It was a great story that we created a [Florida] domestic industry,” Rollins said. “Until it wasn’t.”

Then-Gov. Charlie Crist and the Florida Legislature responded by approving a dramatic expansion of the state-backed reinsurance fund to lower costs for private insurers and suppress prices. They froze rates for Citizens to help it compete for business and force down prices of private insurers. Frustrated by being unable to obtain rate increases they said were essential, big national home insurers kept shedding policies and many set up “pup” units to isolate Florida risk from its national business. Seeing an opportunity, entrepreneurs launched 13 companies, supported by a state program that matched private investor capital with state funds, Rollins said.

A lull

Florida dodged a bullet for the next decade when no hurricanes made landfall, which was unprecedented. (Historically, the state is hit by a hurricane roughly every two years, and a major one every five, experts say.) The lull helped Florida’s insurance machinery run more smoothly and provided enough time to replenish Citizens and the FHCF. By June 2015, Citizens, which had become the state’s largest insurer, paid off its debt, discontinued surcharges on policyholders, and, over a period of years, “depopulated” by turning over roughly 1 million policies to Florida carriers. Private-market companies picked up these policies, and built profits and market share. The good times ended in 2017, the year Hurricane Irma entered southern Florida and swept north, affecting all 67 counties and causing tens of billions of dollars in damage. Irma was followed by 2018’s Michael, only the fourth Category 5 hurricane in modern times to hit the United States — and third to hit Florida — which virtually wiped away Mexico Beach and crushed parts of the Panhandle. Concurrently, what one insurance lobbyist referred to as an “entrepreneurial cottage industry” of lawyers began exploiting legal loopholes to win major damage awards. Insurers were caught blindsided by the changing landscape and didn’t fully account for excess litigation, which became a financial tsunami as big as a real major storm.

“The lack of storms between 2005 and 2016 hid that fragility,” said Charles Nyce, associate professor of risk management and insurance at Florida State University. “Storm activity since 2016 along with burgeoning fraudulent claims have led to substantial market destabilization.”

Litigation matters

The amount of property insurance litigation in Florida has soared ever since, according to data from the Florida Office of Insurance Regulation (OIR) and the National Association of Insurance Commissioners. In 2021, 38% of the time a Florida home-insurance company denied a Floridian’s claim without payment it was sued (Figure 5). The typical rate of other states: 1% to 2%. Florida’s U.S. share of all home-insurance lawsuits filed was 76% in 2021, yet Florida policyholders submitted only 7% of U.S. claims. All told, according to the most recent yearly OIR data, Florida insurers spent $3.1 billion to defend against lawsuits, costs that are eventually passed to homeowners in higher premiums.

In 2021, 38% of the time an insurer denied a claim in Florida the homeowner sued.

*Does not include Citizens Property Insurance Corp., which reported 10,367 suits in 2021.

Figure 5 – Sources: National Association of Insurance Commissioners, Citizens

Don Matz, who was president of Gainesville-based Tower Hill Insurance until last summer, said, “Florida is naturally more expensive because of the hurricane risk. But it’s the litigious environment that has really driven the problem for the insurance market for the last five years.” Joe Petrelli, president of Demotech, an analysis firm that rates the financial health of most Florida insurers, cited the example of St. Johns Insurance Co., which regulators declared insolvent, leaving some 150,000 customers scrambling to find new policies last year. In 2021, St. Johns had 4,000 new litigated homeowner-insurance claims. That same year the entire state of California had 3,600. “St. Johns was litigated to death,” he said.

How’d it happen? Florida’s expanding legion of plaintiff attorneys, who on TV and radio tout lucrative awards they’ve won for clients, have become more prolific in litigating property disputes. Such suits often start after a home suffers some unexpected damage, not only from hurricanes but a growing number of convective storms. Unlike most states in which each side usually pays for their own lawyers, Florida law has allowed lawyers to reap legal expenses from insurance companies if they receive a jury award that is just $1 more than an insurers’ final settlement offer, Nyce and others explained. Yet if they lose they aren’t obligated to pay the insurer’s legal costs. The law was put in place to give a slingshot to David to fight Goliath, and discourage insurance companies from dragging their feet on policyholder claims. But insurers and other critics say the law resulted in tens of thousands of often questionable cases. Matz said every Florida company can provide anecdotes of lawsuits that started as routine $15,000 disputes that ended up costing many hundreds of thousands of dollars. Insurers haven’t been able to raise rates fast enough to catch up with the faster-spinning hamster wheel, Rollins said.

Meanwhile, reinsurance companies that support Florida insurers — many of which are based in Bermuda and largely unregulated — aren’t happy that they remain on the hook to pay for costs that keep rising many years after storms have passed. For example, the estimated insured losses in Florida from Irma, which sparked the filing of 774,327 damage claims starting in 2017, soared to more than $21 billion from the original estimate of $4.7 billion, according to OIR data. Industry experts said during this year’s reinsurance policy negotiation period insurers face steeply higher costs for reinsurance, which already account for roughly half of a typical Florida policy.

Sessions were special

To stabilize the market, lawmakers largely gave insurers what they’ve been wanting for years: curtailing the incentive for lawyers to file lawsuits. The most consequential change was erasing Florida’s one-way attorney fees and the practice of assignment of benefits. “If this isn’t a silver bullet I don’t know if there ever will be” a solution to the litigation problems, said Kevin Comerer, lobbyist who represents the Florida Association of Insurance Agents. “You’ll have to go to an unregulated or a socialized market.”

Separately, lawmakers made changes to puncture Citizens’ ballooning policy count, including incrementally mandating all Citizens policyholders carry flood insurance, which could cost some homeowners thousands of dollars a year. This is after previously permitting Citizens to ratchet up rates as much as 15% each year from a previous annual rate hike cap of 10%. Finally, the new law allows insurers to offer arbitration-only policies to policyholders, which means they give up the right to a jury trial. In exchange insurers are required to provide an “actuarially sound” discount to policyholders, who can still elect a higher-priced policy and retain the right to go to court. “It will be interesting to see what kind of premium reduction results,” said Robert Jerry, former dean of the University of Florida College of Law, whose “Understanding Insurance Law” textbook is used by law schools nationwide.

Real estate concerns

Throughout 2022, lawmakers heard from a growing chorus of those who feared the deteriorating home-insurance business was beginning to affect the real estate market. It almost goes without saying that insurance undergirds the real estate market because without insurance, banks won’t issue a mortgage; without a mortgage, most prospective homeowners can’t buy a home.

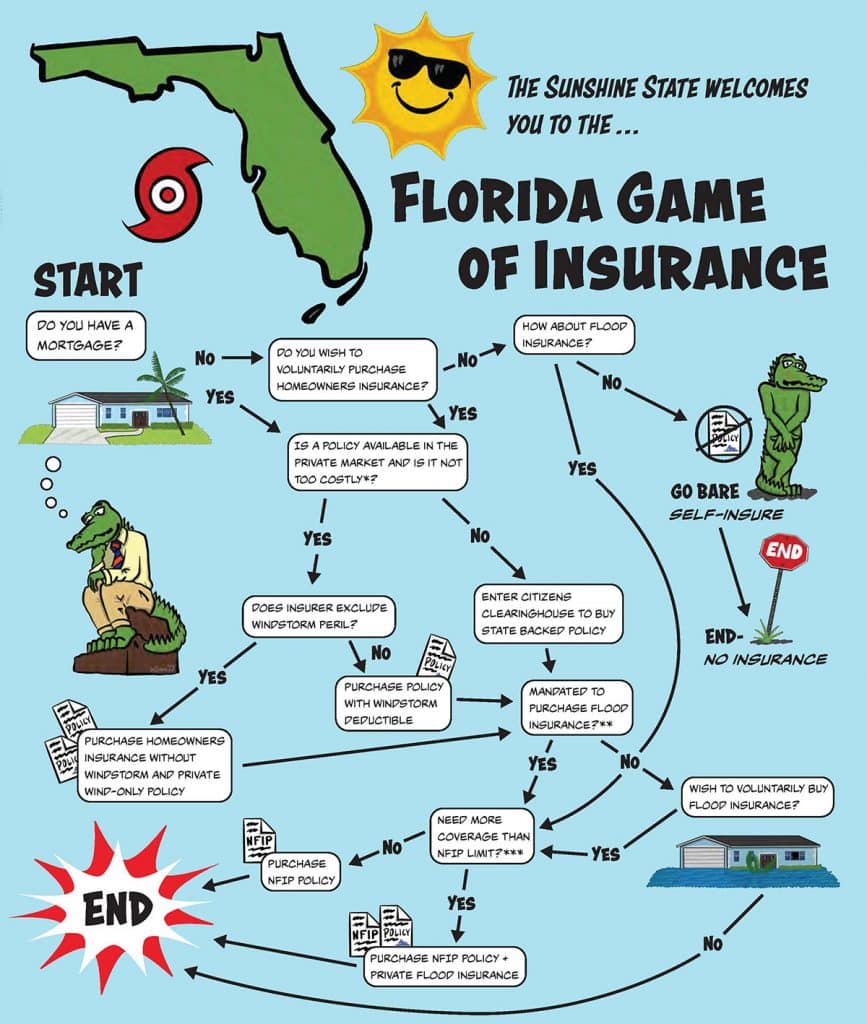

Cyndee Haydon, a Maderia Beach real estate agent and chair of the National Association of Realtors insurance committee, said insurers are pickier about writing policies, especially on older houses. She told of a seller who was forced to replace a house’s roof so an insurance company would write a policy and allow a buyer to close on a mortgage. “Normally you wouldn’t have to do that,” she said. Haydon was among numerous sources who told a personal insurance story. After her company dropped her policy, she had no choice but to pay Citizens $5,800 to insure her cement block home on the beach this year. She also pays $6,500 a year to the National Flood Insurance Program, the federal plan that provides most flood insurance policies nationwide. All told, she now forks over annual premiums of $12,300 to cover a 1950s house with a replacement value of roughly $350,000. “I’m worried about how much it will be next year.” (See Florida Game of Insurance on page 19 for the maze consumers travel to buy a policy.)

A retired Atlanta lawyer said he and his wife are considering “going bare,” meaning without insurance, after their carrier denied a claim to repair damage caused by Ian to their second home on Gasparilla Island. This is possible because they have no mortgage. A public adjuster the couple hired shared a lengthy document with photos and an itemized list of damages, including roughly $50,000 to the roof. The lawyer, who asked not to be named as he still is negotiating with his insurer, said they may have been better off investing the tens of thousands of dollars they have spent over 20 years without filing a claim. If their home is ever damaged, they’d pay for repairs out of pocket. As of Jan. 20, nearly one-third of the 380,000 claims filed after Hurricane Ian were closed by insurers without them making a payment, according to the OIR.

Too far?

Lawyers, consumer advocates and a minority of state lawmakers expressed concerns that the balance has now swung too far against consumers. Amy Bach, an attorney and executive director of United Policyholders, a nonprofit that advocates for the rights of insurance policyholders, said, “I’m not naïve enough to say that all those lawsuits are justified. But from my experience, most people after they get hit by a disaster don’t want to get involved in a lawsuit. They just want their house repaired.”

As ever with Florida property insurance, how things shake out is anybody’s guess, but one thing clear is policyholders shouldn’t expect lower premiums anytime soon. In the meantime, it is worth considering that things could always be worse. Last summer’s Ian, one of the most powerful hurricanes ever to hit Florida, wasn’t the Big One that the industry has long feared. Had Ian not veered to the Fort Myers area but instead hit Tampa Bay — as it was initially projected — estimated insured losses would have topped $100 billion, according to Clark’s estimate.

Jerry summed it all up: “We’re living in a risky state. As Floridians, we are going to pay more for insurance. There’s no two ways about it.”

Footnotes:

- Results of 52 Florida-based insurance companies, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence data provided by Citizens Property Insurance Corp. Doesn’t include Citizens.

- In 1993, Allstate and State Farm groups wrote more than 50% of Florida’s home insurance, according to a 2019 paper in the Journal of Insurance Regulation. Today, State Farm Florida has 6.7% and Allstate’s Castle Key Florida subsidiary has 2.6% of state market share, according to AM Best.

Location and age matter — a lot

A home’s age and its location account for a vast difference in the price Florida homeowners pay for insurance. Adam Myers, co-owner Ponte Vedra insurance broker First Coast Insurance Services, compared price quotes on basic policies for four homes with comparable replacement values in two regions of the state. Two homes were inland of St. Augustine in Northeast Florida and two were on Marco Island in Southwest; we chose homes built recently vs. older ones.

Here’s what we found. Price: The lowest quotes varied from $580 to $6,241. Age of home: New homes, built to meet more stringent building codes, received quotes $1,571 to $1,611 less than the older ones in the same market. Marco Island homes were about $4,000 more than the St. Augustine homes with comparable ages. Availability: Just four of the roughly 10 companies Myers checked provided a Marco Island quote; all quoted St. Augustine. Insurers: The best prices came from relatively little-known Florida-based firms most people never heard of. The good news: each received a competitive quote, so none were relegated to state-owned Citizens.

Myers emphasized the value of strengthening homes and obtaining a wind-mitigation inspection. Since 2003, Florida law has required insurance companies provide specified policy discounts for consumers whose homes have windstorm resistant features. These may be visible — like hurricane windows and the shape of the roof — or hidden, such as the method of attaching roofs to rafters and rafters to perimeter walls, and the presence of a secondary water barrier. Discounts go to homes with hip roofs — pyramid-shaped roofs that better withstand high winds than traditional gable roofs. Myers noted that Vyrd Insurance Co., a Florida startup, initially quoted a premium of $18,000 on the older Marco Island home. The price dropped to $6,241 after applying wind mitigation credits. (See Florida Game of Insurance below for the steps Floridans take when shopping for a policy.)

Price quotes of home-insurance policies vary widely

| Location | Year built | Annual premium | Company |

|---|---|---|---|

| St. Augustine (18 mi from beach)* | 2021 | $580 | American Integrity Insurance of Florida |

| St. Augustine (11 mi from beach)** | 2005 | $2,191 | Edison Insurance Co. |

| Marco Island (2.2 mi from beach)*** | 2022 | $4,670 | American Integrity Insurance of Florida |

| Marco Island (3.3 mi from beach)**** | 1998 | $6,241 | Vyrd Insurance Co. |

Note: Quotes are for multi-peril policies for homes with replacement costs ranging from $341,000 to $400,000. Policies cover windstorm and other customary coverages, and carry a hurricane deductible of 2%. None include flood coverage. Wind-mitigation and other credits: *$1,060 | **$2,179| ***$20,668 | ****$14,130 (roof replaced in 2022)

Source: First Coast Insurance Services, Ponte Vedra

larger image | image description

*Can only purchase policy from Citizens Property Insurance if no private policy is available for less than 120% of Citizens’ rate

**If you live in a flood zone or are a policyholder with Citizens (phased in over four years starting April 2023)

***National Flood Insurance Program policies have a $250,000 limit

Charles Boisseau is editor of Due Diligence.

Related stories

For the media

Looking for an expert or have an inquiry?

Submit your news

Contact us

Follow us on social

@ufwarrington | #BusinessGators