What to do with Fannie & Freddie

High on the list of questions facing the U.S. financial system is what to do with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. These government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) have been path-breaking, powerfully successful institutions. They were crucial in transforming housing finance from a 19th-century tradition of local mortgages into a system of mortgage-backed securitization that brings capital from every corner of the globe to American homes.

Since 2008, however, both organizations have been in conservatorship under the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), a step taken to avoid insolvency that might have collapsed the U.S. housing market. Conservatorship was expected to be short-term until the GSEs could be dismantled and replaced with a new housing finance system. Seventeen years later, their future remains unclear.

Since their launch as freestanding entities in 1968 (Fannie Mae) and 1970 (Freddie Mac), the GSEs have grown to where their single-family mortgage securities cover more than 40% of all U.S. home mortgages, and an even greater share of mid-size, “prime” loans. They also now hold about half of all U.S. multifamily mortgage debt. As of 2025, the outstanding securities and mortgage loans of the GSEs total about 7.7 trillion—making them the third-largest single-source issuer of financial securities in the world, exceeding the debt of every company and every government except the United States and Japan. See the GSEs’ combined balance sheet in Figure 1. The central question remains whether these are private entities temporarily under government control or federal entities in practice.

Structural challenges

Despite—or perhaps because of—the GSEs’ success, their original mission to expand mortgage access and affordability began to clash with the drive for profits. Design flaws emerged as the enterprises gained authority to issue publicly traded stock (Fannie Mae in 1968 and Freddie Mac in 1989). A February 2011 report to Congress by the U.S. Treasury and the Department of Housing and Urban Development, summarized by Laurie Goodman of the Urban Institute, highlighted key shortcomings:

- Their charters required the promotion of market stability and access to mortgage credit. But their private shareholder structure encouraged management to take excessive risk to retain market share and maximize profits, putting taxpayers on the hook.

- An implicit government backing conferred unfair advantages, including preferential tax treatment and, more importantly, lower funding costs because markets assumed the government would bear large losses.

- Capital rules were looser than for private institutions—only 40 basis points of capital for every $100 insured—allowing lower guarantee fees but leaving too little cushion to absorb losses.

- The regulator, the Office of Federal Housing Enterprise Oversight, was structurally weak and ineffective. It lacked adequate enforcement tools and authority to set capital standards or meaningful stress tests. Aggressive lobbying blunted efforts to increase oversight.1

1) Laurie Goodman, Recapitalizing the GSEs through Administrative Action: An Assessment, Urban Institute, April 2025.

Source: Congressional Budget Office, An Update to CBO’s Analysis of the Effects of Recapitalizing Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac Through Administrative Actions (December 13, 2024).

With an implicit government guarantee, privatization could set up the same situation that led to the GSEs’ initial failure in 2008.

Failure and conservatorship

The Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008 created the FHFA as the new regulator with power to place the GSEs into conservatorship and to rewrite their rules. FHFA imposed conservatorship immediately.

At the core of the conservatorship was a U.S. Treasury contract with each GSE, a preferred stock purchase agreement (PSPA), that both regulated the enterprises and defined a Treasury credit line. If a GSE’s quarterly net income went negative, Treasury would grant a “loan” equal to the shortfall, in return for an equal amount of senior preferred stock. The maximum cumulative credit line began at $100 billion for each GSE. While the limit varied over time, the combined outstanding amount settled around $192 billion in recent years.

Progress to date

During conservatorship, both GSEs reduced risk to the economy and improved productivity. Each cut its asset portfolio—laden with higher-return but riskier loans—from roughly $800 billion to below $225 billion. Additionally, they expanded credit-risk transfer programs that sell a significant share of default risk on their portfolios and guarantees to private investors. The guarantee, a core product of the GSEs, assures investors the timely payment of scheduled interest and principal from the loans in the securities sold. GSE efficiency advanced through creation of powerful, GSE-wide, information systems for all aspects of mortgage security creation, management and disposition.

In parallel, has been the growth of the to-be-announced (TBA) market for GSE and Ginnie Mae mortgage-backed securities. TBA securities have become, in effect, the only debt instruments worldwide that rival U.S. Treasurys in liquidity.

Another milestone was the uniform mortgage-backed security (UMBS), introduced in 2019 and now issued by both GSEs. Evidence suggests the UMBS added enough liquidity in the TBA market to measurably lower interest rates on conforming conventional home mortgages.

It is important to note that virtually all loans touched by the GSEs (and by Ginnie Mae) are fixed-rate, level-payment and freely prepayable. About 95% of U.S. home mortgage loans for households in the lower 80% of the income distribution are of this type, and many consider this availability vital to homeownership.2 The cost, and possibly the availability, of such loans is inherently dependent on the efficiency and stability of the GSE/Ginnie Mae market system.

2) Yu-Ting Chiang and Mick Dueholm, Which Households Prefer ARMs vs. Fixed-Rate Mortgages? Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, February 6, 2024.

Why change now?

Several forces are pushing for change.

- Speculation: Some holders of legacy stock are betting that a return to private status would yield windfall gains, potentially hundreds-fold. Dormant-stock accumulation and lobbying for privatization reflect that bet, often without regard to risks or costs to the public mission.

- Governance: Without the influence of private owners wielding voting power, the GSEs are largely subject to the FHFA, which, in large measure, is subject to the pleasure of the presidential administration. Given the extreme influence on housing finance and the amount of cash flow through the GSEs this may invite manipulation for political or personal objectives, to the possible detriment of the public mission.

- Monopoly risk: The GSEs’ dramatic recent improvements move them toward a natural monopoly. Their progress in efficiency and economies of scale have made competing with them increasingly difficult. Therefore, they could jointly engage in monopoly pricing, with little motivation for further innovation, and arguably should be regulated as a monopoly. Efficiency is gained at competition’s loss.

- Loss of entrepreneurial spirit: Former GSE leaders worry about “HUDification” — the chronic illnesses that tend to plague long-term bureaucracies, including lack of innovative spirit, neglect and underfunding. They see the GSEs as perhaps the only entities that have the capacity and leverage to encourage transformative innovation throughout the home-building industry.3

3) Urban Institute panel discussion: Recapitalizing the GSEs through Administrative Action: Former CEOs Explore Conservatorship Release, March 18, 2025.

Barriers to change

The only way to change the current situation is administrative action given that Congress has repeatedly failed to legislate a new framework. Yet the most important need is legislative clarity on any Treasury guarantee, which isn’t in the cards. Privatization also requires recapitalization. Despite strong financial performance under conservatorship (over $20 billion of positive net cash flow per year in recent years), and even with supportive treatment by FHFA, it will be fraught with uncertainties.

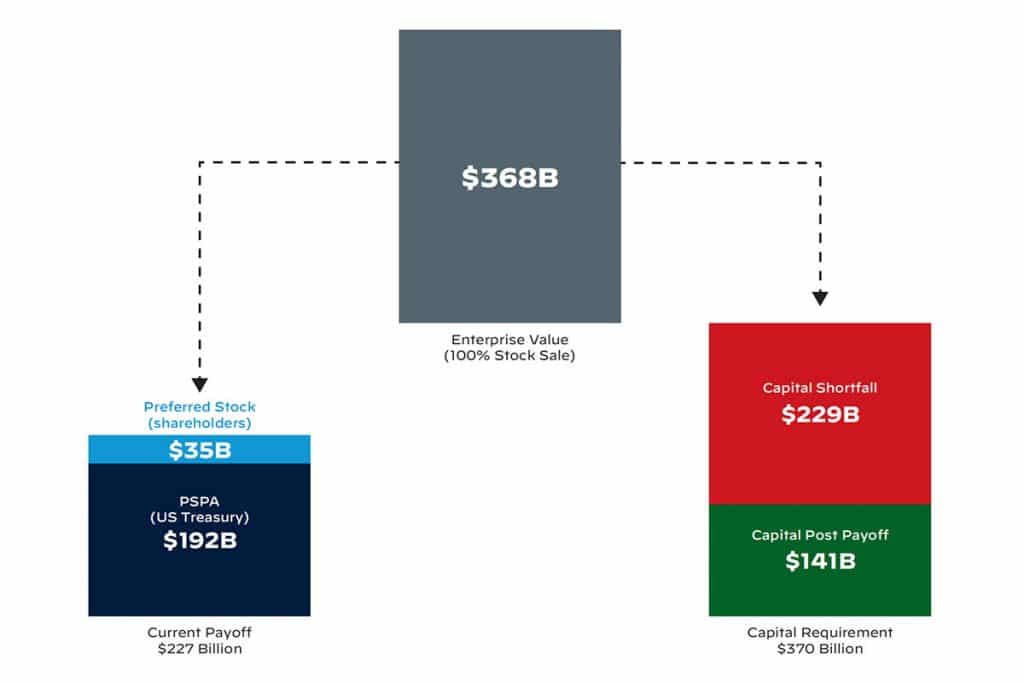

Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projections suggest the likely equity value of the GSEs by early 2027 – about $368 billion – still falls short of what’s needed for conversion. Recognizing the challenges of a 100% enterprise transaction and using the CBO estimates, Figure 2 demonstrates that privatization proceeds could retire the preferred stock or capitalize the new entity but will not meet both needs. Complicating matters: there are two enterprises that effectively function as one. In the private sector, that runs into antitrust constraints; rechartering or legislative authority to coordinate—or fully merge—may be required. Former CEOs caution that a full merger would be harder than it looks, given distinct institutional histories. Any privatized entity would be a new venture in a changed market environment.

A proposal now being considered is a $30 billion initial public offering. But some observers argue that privatization and the public offering to obtain the necessary capital must be accomplished as a single event. Otherwise, the investors would be putting capital into an enterprise requiring major overhaul (integration of two companies), and without investor control. If the public offering must be a single event, then it is unprecedented in the extreme. The largest public offering in history was by a stable, established business, Saudi Aramco, 2019 (approximately $29 billion including follow-up sales), and this issue represented only 1.5% of the enterprise value. If these analysts are correct, the GSE offering would need to be the largest in history by a factor of 12, creating enormous unknowns and risks.

If the GSEs are privatized, the implicit government guarantee looms. Without it, most observers expect mortgage rates and volatility to rise, potentially weakening or destroying the TBA market and possibly the predominance of the fixed rate, level-payment home loans. With it, there is concern that privatization, in the long term, sets up the same situation that led to the initial failure of the GSEs in 2008.

Figure 2 – Projected 2027 GSE recapitalization path

Looking forward

The future remains unsettled, with strong forces pulling in different directions over whether the GSEs should be public or private and with or without taxpayer guarantees.

One option is to slightly modify the current arrangement to be more permanent and convert the GSEs into full government agencies. Public-interest groups, focused on housing shortage and affordability, emphasize the value of stable mortgage markets and low rates in building household wealth. They also note that private markets tend to favor larger loans and lower-risk borrowers. Supporters point to the GSEs’ track record of innovation and improvement since conservatorship began. A public-agency approach would carry an explicit government guarantee.

Private-market advocates argue that competition best drives innovation and economic efficiency. This option unloads mortgage market operations from the government allowing it to focus directly on the acute housing challenges. However, there is no current belief that private GSEs can survive or support the mortgage market without payment guarantees (implicit or explicit).

If privatization removes the U.S. government guarantee, the GSEs are likely to become noncompetitive, disrupting housing and the broader economy. Social objectives of mortgage access and affordability disappear without the guarantee. If privatized without a guarantee, GSE securities will be sharply downgraded and the river of capital for U.S. housing could become a small stream.4 Alternatively, accepting the current public structure of the GSEs solidifies a giant government agency conducting major private market finance under political, rather than financial, direction.

Despite the pressure to change the 17-year limbo conservatorship, it seems the GSEs will remain in the U.S. government control for years to come. A positive take is that most housing finance experts seem to agree that the largest immediate problems with the pre-conservatorship GSEs have been substantially mitigated, giving a better outlook for the next few years, even if they remain quasi-government agencies. There is little question that the GSEs have been highly effective in executing their role in the economy and are well prepared to continue – public or private.

4) Jim Parrot and Mark Zandi, “Fannie and Freddie’s Implicit Guarantee-Another Iceberg on the Path to Privatization,” Moody’s Analytics, January 2025.

Wayne Archer, PhD., is a professor emeritus at the University of Florida Warrington College of Business.

Related stories

For the media

Looking for an expert or have an inquiry?

Submit your news

Contact us

Follow us on social

@ufwarrington | #BusinessGators