Banking on mitigation

In the Fall of 2018, Clay Thompson was living in Frankfort, Ky., when he got a call from an old Air Force buddy who was enjoying the good life in Florida. But his friend was having trouble obtaining a permit to build a backyard swimming pool at his home in Lutz, a fast-growing community north of Tampa.

Photo above: The Withlacoochee Wetland Mitigation Bank is in the Green Swamp, a designated “area of critical concern” by the state. Factors in site selection for a bank include not only the demand for credits but proximity to other conservation areas. Photo credit: Environmental Consulting & Design

It turns out his plan to remove several cypress trees to make room for the pool would destroy a small wetland, a natural area that is protected and highly regulated under state and U.S. environmental laws. His only viable option was to write a fat check to a bank the likes of which he had never heard of — a wetland mitigation bank.

Thompson, a retired Air Force major, couldn’t have predicted his friend’s guitar-shaped pool would strike such a chord that he’d launch a startup and relocate to Florida. But that’s what he did a few months later when he and a few wealthy private investors created one of Florida’s newest wetland mitigation banking companies. They bought 400 acres near the Ocklawaha River in Polk County, spent several years securing regulatory permits and last year began selling “credits,” which is the currency used by mitigation bankers. “I probably couldn’t define what a mitigation bank was,” Thompson recalled. “Unless you need them you don’t know what they are.”

The public may know little about them, but wetland mitigation banks can play a big behind-the-scenes role in making a real estate development happen. Bankers create, enhance and preserve wetlands on large tracts of property and then sell credits to offset a development on land in the same water basin that regulators determine is “wet” — no matter if the development is a condo tower, a roadway or a backyard pool. Experienced real estate developers know these waters: They understand they face legal and regulatory problems, and costly construction delays, if one of their projects harms a wetland, so they try to avoid them. If they can’t find a workaround, their best option is usually to go to a wetlands mitigation banker to buy credits.

But lately a different sort of credit crunch is making things choppy for developers. Wetland mitigation credits are drying up in some of Florida’s fastest-growing areas and prices have spiked to record levels. Participants cited several factors for the credit squeeze, including higher demand from increased development and the burdensome process for banks to obtain operating permits. The number of new banks permitted per year has dropped off in recent years and just two banks were approved — including Thompson’s Missing Link Mitigation Bank — in 2022 (Figure 1), according to the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), one of many agencies that regulate and permit mitigation banks. The situation has prompted worries over project delays and calls for legislative and regulatory reforms to shake loose more credits and speed approval of new banks. “One of the things we’re looking at now is a shortage of credits throughout the state,” state Rep. Toby Overdorf told regulators in a recent meeting of the water quality subcommittee. He is a Palm City environmental consultant.

Source: Florida Department of Environmental Protection

To better understand the mitigation banking business and explain what’s going on, we reviewed research literature, government data and reports, and spoke with two dozen participants across the industry, from bankers and environmental consultants to regulators and developers. They provided differing perspectives on how the market operates in Florida, a state that has helped pioneer what has become a multibillion-dollar industry.

Despite being underpinned by a massive regulatory and environmental framework, mitigation banking comes down to business. Bankers said they are long-term investors motivated both by profit and a desire to preserve biodiversity. “It’s that sweet spot,” Thompson said. “Where is that balance in which you protect wetlands and allow development to keep going?”

Background

Throughout history people have dredged, filled and otherwise destroyed wetlands, which were once thought of as little more than disease-provoking wastelands. This changed most dramatically in 1972 with the passage of the U.S. Clean Water Act (CWA) and subsequent environmental laws that introduced the concept of “no net loss” of wetlands. The law recognized the environmental and economic value of these watery areas, which scientists consider one of the most productive ecosystems in the world, akin to a coral reef or a rainforest. Wetlands deliver ecological benefits that include flood protection, water storage and purification, and habitat for wildlife. Generally, U.S. law prohibits landowners from harming a wetland, but if impacting one is unavoidable, developers are required to pay “compensatory mitigation” to create or restore a functionally equivalent ecological area in the same watershed.

When it comes to mitigation banks, researchers trace the concept to the early 1980s when the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service envisioned conservation-minded landowners selling wetland credits to make mitigation more successful, and to reduce a developer’s costs and liabilities. A decade later the mechanism came to Florida with the passage of a mitigation banking law and accompanying regulations. Mitigation banking has since become the go-to way to offset losses of wetlands, which make up roughly 29% of the land in Florida[1], more than any other state and home of the world’s most famous one, the Everglades.

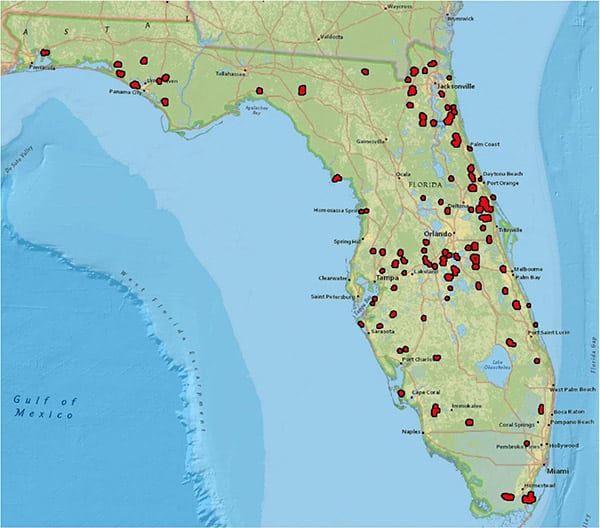

Since 1993, when Pembroke Pines Mitigation Bank in South Florida received a permit, the Florida market has grown to 131 mitigation banks, encompassing a total of 227,000 acres. Florida banks range in size from a couple hundred acres to the 22,000-acre Farmton Mitigation Bank in Volusia and Brevard counties, which is owned by a Chicago-based investment firm. The second largest is the 13,249-acre Everglades Mitigation Bank, owned by Florida Power & Light.

Regulatory officials said 30 new mitigation banks are in various stages of the permitting process, which officials indicated will relieve the shortage of credits. But it’s unclear when those banks will begin operations. It can take two years to obtain a permit from DEP or one of the state’s five water management districts, and more than five years for a federal permit from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, said Eric Olsen, a Tallahassee lawyer who specializes in environmental law and works on permitting issues with many bankers. State and federal programs require separate applications and separate permits, which invariably stretches the permitting process.

UMAM

In addition to lawyers, every mitigation banker works closely with environmental consulting firms, which provide permitting and many other services. Consultants create initial restoration and longer term maintenance plans that spell out what bankers must do and at what interval to achieve ecological “lift” to earn credits they can sell on the marketplace.

The work includes conducting prescribed fires, removing invasive species, restoring native vegetation to provide forage and cover for wildlife, and improving natural hydrologic flows that were previously altered, said Sarah Nelson, owner of Environmental Consulting & Design (EC&D) in Gainesville. Her company also manages roughly 50,000 acres for mitigation banks and evaluates properties for bank suitability, which may include reviewing aerial maps to determine the natural state of the land before its use changed to, say, a farm, cattle ranch or a monoculture of pine trees.

An important part of the work is using a scientific tool, called a Uniform Mitigation Assessment Method, or UMAM, to determine how many credits a banker’s property can generate long-term. The system evaluates a land’s ecological condition, such as its hydrology, location, vegetation composition and mitigation risk. The concept gets at what bank customers pay for. They aren’t paying for acreage, exactly, but a bank’s ecosystem services — the ecological functions provided by creating or restoring a wetland in a bank. The calculations invariably show a developer needs to purchase credits equivalent to improving more acreage in a bank than they impacted. Typically, it takes three, four or more acres to mitigate for the loss of one acre of wetlands, Nelson said.

Pricing and availability

Mitigation bankers face tons of regulations, but there’s no regs on what they can charge for a credit, so prices go higher where there’s more demand. These days the cost ranges from $130,000 to more than $400,000 per credit, said Victoria Colangelo, owner of Mitigation Banking Group, an Orlando broker of mitigation credits. Why the wide range? “It depends if there’s only one bank in the basin or not,” she said. “Florida has 86 basins, and some have multiple banks operating while others have one or none.”

Banks are authorized to operate in only one specific geographic area dictated by water basin. This means a bank servicing one basin can’t sell credits in another, so prices may spike in a basin with lots of demand; and a bank with lots of credits can’t cross over and fill the need.

The wetland banks were running out of credits. So, guess what happens when supply and demand get out of balance? The price shot up on us.

Let’s review some numbers, courtesy of Kolter Mixed-Use LLC. Recently, Kolter permitted a Wildwood project in a basin where $140,000 credits were widely available, said Troy Simpson, president of the affiliate of the real estate firm Kolter Group. The project’s UMAM score was 5.25, meaning they needed to buy the same number of credits for a total of $735,000. In contrast, their consultant advised they’ll pay $225,000 a credit at a planned project in northern Manatee County with a UMAM score of 2.57. The total cost came to $580,000. Another example: Kolter paid 60% more than it budgeted to offset wetland impacts at a residential project in south Brevard County. “We had budgeted $125,000 per credit but due to only one bank having credits available, and another bank running out of herbaceous credits, we are now paying $200,000 a credit,” Simpson said. The total to buy 11.48 credits: $2.3 million.

David Kern, managing director of Foundry Commercial Tampa, said his company faced sharply higher mitigation costs than budgeted at its Lakeside industrial complex under development in Polk County. “The wetland banks were running out of credits,” he said. “So, guess what happens when supply and demand get out of balance? The price shot up on us.”

Foundry bought credits from Alafia River Wetland Mitigation Bank, one of only two banks operating in a 335-square-mile river basin that stretches from western Polk County through Hillsborough County to Tampa Bay. In the past few years, the bank has nearly doubled the price of a credit to $225,000, said Patrick Mims, vice president of T. Mims Corp., the bank’s owner. His father, Tom, said, “The market is on fire.” A former accountant, the elder Mims created the bank five years ago by carving out 400 of the 9,000 acres he owns and uses for cattle operations, sand mining and property sales.

Ashton Mears, the government affairs director for the Florida Home Builders Association, said builders working in specific water basins in the Jacksonville area and Miami-Dade County face the most pressing credit shortages. “We think Tampa will be next,” she said.

The subject of dwindling credits and high prices was the main topic at a Florida Association of Mitigation Bankers workshop in Jacksonville on Sept. 7. Olsen, formerly an attorney with the St. Johns River Water Management District, moderated a session on addressing the shortage of credits. Participants discussed the merits of a “proximity factor” tool the Army Corps has begun using to allow federally permitted banks to sell credits outside assigned water basins. A bill supported by the home builders’ association to achieve something similar was filed at the state Legislature but died in committee. Consultants and bankers also debated a more controversial idea of opening private-public mitigation banks on public lands, a concept one consultant said had bad “optics” that made it politically infeasible. Just by the fact you’re allowing a bank on public lands “you look like you’re assisting developers to destroy wetlands,” he said, even if theoretically it’s an even exchange.

Reid Hilliard, environmental resource program manager at the St. Johns River Water Management District, indicated the district was expediting a stack of applications for new mitigation banks. “The market is responding, but there is a lag in getting new mitigation banks on,” he said.

Wearing both hats

Despite the dwindling credit supply and higher costs, few traditional developers have decided to take on additional risk by creating their own mitigation bank. In addition to the many years it takes to get one permitted, running a bank is not in their wheelhouse. Studies have found that mitigation banks are generally more effective than developers in creating and maintaining protected wetland areas themselves. “From an environmental perspective, a restoration project in a mitigation bank is more likely to be successful,” wrote Royal Gardner, a law professor at Stetson University and an expert in wetland law and policy. Olsen said when a developer buys credits “the legal responsibility for the mitigation site now rests with the mitigation banker.” Permits require the preservation of land in a bank in perpetuity. Chris Ward, vice president of land at Meritage Homes, said its “preferred method is to buy credits from a mitigation bank to offset impacts. It’s easier to manage,” he said. And once you purchase credits “you move on with your life.”

There are exceptions. A few developers operate their own banks, such as Avery Roberts, a long-time Lake Butler developer and owner of timber and farmlands. In 2020, he bought the 3,000-acre Longleaf Mitigation Bank in Nassau County with plans to offset wetland impacts on his projects and sell credits to other developers. “We wear both hats,” he said. In October, the bank was out of state credits, but Roberts expects the St. Johns district to approve 34 credits by yearend after Longleaf successfully completed a restoration phase that included prescribed burns.

Roberts also increased the bank’s revenue stream by expanding into species conservation. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission granted him a “recipient site” permit to accept up to 250 gopher tortoises on the sandy portions of the property. The burrowing “keystone” animals are deemed a threatened species by the state. Developers and transportation agencies pay $4,000 to $10,000 each — up from roughly $2,000 two years ago — to relocate a gopher tortoise to such a property. In October, Roberts said he had only a few spots left.

Many mitigation bank owners said they don’t consider themselves passive landholders, but developers of a different sort. “I’m a developer,” said Bill Schroeder, who owns Loblolly Mitigation Bank. “It’s no different than being a developer of apartment complexes.”

Thompson, the founder of Missing Link, has become something of an expert in the business of Florida banks. Last year he earned a doctorate in environmental management from Colorado Technical University and interviewed 11 Florida mitigation bankers for his dissertation, a study on bank site selection in Florida. Missing Link is in the southern Ocklawaha River watershed on property once used to raise cattle, and it’s adjacent to a Cemex sand operation. Its name highlights its additional role of connecting two major conservation areas, making for a miles-long wildlife corridor. The property contains potential habitat for 23 state or federally threatened and endangered species, according to state regulators. A trail camera on the property recently recorded one — a Florida black bear.

Thompson said he is optimistic enough about the bank business that he is actively scouting opportunities to invest in another bank or to start a second one. Although he well knows getting a new bank going involves a three-to-five year “crunch” before it can generate its first dollar “it’s a good long-term investment,” he said. “It keeps the real estate engine and the development engine chugging along. And it helps the environment.”

- Conservation Priorities and Environmental Offsets: Markets for Florida Wetlands; Daniel Aronoff and Will Rafey; National Bureau of Economic Research, July 2023

Charles Boisseau is editor of Due Diligence.

Related stories

For the media

Looking for an expert or have an inquiry?

Submit your news

Contact us

Follow us on social

@ufwarrington | #BusinessGators